In our last edition of How To Kill Your Tech Company, we explored just some of the various ways corporate edgelord Elon Musk managed to crater a supposedly $44 billion dollar company by making, and this will not be surprising for anyone who's followed Musk's other recent career moves, just about every executive screw-up it's thought possible to make and at least one that was considered nearly impossible to pull off. What can we say? The man has a gift.

This time let's talk about Vice. Specifically, Vice Media, which filed for bankruptcy in 2023 and which announced in February 2024 that they were closing down their websites to—and yeah, it was as weird as it sounded—instead distribute their content by "partnering" with other companies to—you know what, forget trying to explain it here. You can read about that announcement here if you missed the whole debacle and no, it's not really any more coherent now than it was then.

I'm counting Vice as both a media company and a tech company, because once Silicon Valley and the hedge funds got involved with online media any website that included Content was considered Tech because that allowed the enormously pretentious gits brought in to manage them to justify larger salaries and attend a more hedonistic type of parties. Does it primarily exist online? Sure, fine, it's a tech company.

I'm going to warn you in advance, though: We're going to start out talking about Vice as our now-famous example of horrible ridiculous face-planting management failures, but what this post is really going to be about is the reasons why growth-obsessed management of the hedgefundian and brunchlordian and privatequitarian varieties is often a ticking time bomb for their companies even if those executives are competent and well meaning.

They're often not, of course. We are all adults here, ones with W2 forms and favorite music and broken childhood dreams, and we're all perfectly aware that most of the most visible tech and media company failures come at the hands of incompetent grifting lying showboaters, the sort of people who always seem to walk away owning bigger and bigger boats even as each company crashes around them. But the moment any company starts what it intends to be a transformative, company-altering growth spurt, unless it is carried out by talents that do not come along nearly often enough for all such companies to share them, it sets the timer on that company's own eventual collapse.

Hang on, that's the most important point we'll be making here and it needs to be a blockquote:

The moment any company starts what it intends to be a transformative, company-altering growth spurt, unless it is carried out by talents that do not come along nearly often enough for all such companies to share them, it sets the timer on that company's own eventual collapse.

Ah, that's the stuff. But first: Let's talk about Vice.

The collapse of Vice Media is at this point an infamous story, and rather than hashing all of it out here again we can rely in large part on the definitive postmortem by Chris Thompson at Defector. It's worth a full read and a re-read, but of particular note is that the executive team there made a hell of a lot of money burning the thing to the ground, and from the now-public obituaries it seems the burning mostly took the form of trying to grow the company into All The Things while ignoring the advice of all the little peons who had made the company worth investing in the first place.

Vice Media leadership was still self-dealing hefty bonuses in the days immediately preceding its bankruptcy; De, who was given a whopping $200,000 bonus in April one day after The Wall Street Journal reported that 100 or so workers in her department were being laid off, defended her compensation in a July call with angry workers as commensurate with her experience. Vice Media Group's leadership masthead lists 12 of these bozos; that's millions of dollars off the top, much more in salary and bonuses and benefits to C-suite freaks with ill-defined job responsibilities and made-up titles than Defector makes in revenue in an entire year.

The absolute best that can be said of any of Vice's grotesquely enriched stewards over the years is that some of them believed in the value of the work; unfortunately that belief too often took the form of cocaine fantasies of conquering all of media, and inspired its leaders to recklessly burn through actual billions of dollars of investment capital. This was no less destabilizing for Vice's workers, who might otherwise have been able to guide their excellent publications through the industry's tumults if they hadn't been subject to the whims of captains who make Ahab look like Andy Griffith. Meanwhile, the solutions for sustainable digital media are out there, even amid all the carnage and panic of the collapse of the advertising economy.

When it comes to both tech and media companies—God help you if your company is both—this is a phenomenon that's so commonplace it really deserves its own name. Executive team comes in; executive team announces that they know How To Business; executive team proceeds to nail their tongues to the big conference room table; eventually some Executive Rescue Force arrives to bust down the door, destroy the majority of the office furniture, and spirit the newly freed team off to some other company that has classier and more expensive office furniture anyway so yay, everyone who matters gets their happy ending.

Unfortunately all of the names I can come up for this pattern are so adult-oriented that typing them down here would immediately trigger every content filter on the internet, so we'll just set that one aside for the moment.

The second obituary of note came from TechDirt's Karl Bode, who's been relentless as chronicler of the tech sector's aggressive tongue-nailings and enshittification. It's from him we get a categorization for the failure: "Incompetent Fail-Upward Brunchlords."

Numerous Vice editors and staff writers were paid salaries as little as $35,000 a year in New York City (you’d find retirement or financing a home purchase easier with a career at fucking Quiznos). At the same time, executives, clearly incapable of any sort of coherent strategic vision, gobbled up massively outsized compensation not at all commensurate with their workloads or performance:

[...] Even as the company was facing bankruptcy and freelancers and staffers were either fired without severance or (like myself and other Vice freelancers) watched huge segments of their incomes instantly evaporate, legal filings illustrated how Vice executives were handed $11 million dollars — for doing arguably little to nothing — from May 2022 to May 2023.

and:

This, somehow, often gets distorted into the “unforeseen challenges facing modern online media ventures today” by a feckless press pretending to ascertain what went wrong without pissing off management.

When it comes to financing Vice journalism and keeping the lights on, the problem wasn’t the people doing the actual fucking work. Nor is it the costs of doing actual journalism. As noted previously, The equally incompetently managed The Messenger burned through fifty million fucking dollars in less than a year; enough to fund any competently managed modest newsroom for the better part of a decade.

But again, if you read most mainstream analysis of the Vice collapse, executive incompetence is either downplayed or simply nowhere to be found. Instead, the collapse of Vice, like most mismanaged modern U.S. media companies, is often left causation free, somehow the unfortunate, unforeseen consequence of ambiguous externalities in the thankless job of informing the public about factual reality online.

The Vice collapse came because a series of more and more prominent executives came in with instructions to grow an online journalism company into the next US Steel by doing (shrug emoji). Multiple hundreds-of-million-dollar deals with everyone from Fox to Disney provided access to a Matterhorn of money, a good chunk of which went into paying the executive teams raising it. There was, from the outside, never a very clear picture of how Vice's various subgroups and new ventures were going to coagulate into something larger, and from the beginning to the end of it all it appears the workforce producing what the company was actually trying to sell was considered a $35,000-per-person burden that ugh, just kept offering suggestions and pointing out numbers and needing paychecks and ugh how tedious can you get, time for a long lunch to reward ourselves for having to interact with them.

Every company wants to grow; every group of company founders dreams of their new venture being so successful that they can achieve that most precious of all goals: leaving it to do something else, secure in the knowledge that money will still be landing in their bank account regularly. But the effects of growth culture, as management fetish, can be pernicious.

It can quickly turn into a poison, and the conventions of supposed leading-edge Business Doing almost require that it become one. The existing consumer base might come to be seen as group to be exploited or merely a burden that must be placated in order for the company to leapfrog to some newer, possibly imaginary consumer base. The employees who scrambled to bring the company to its current success may now thought of as has-beens; once you grow the company to a certain level now it's time to bring in the More Important People, people who have worked at "bigger companies" and can tell you how to run your successful and expanding business like Boeing or Enron instead of the presumably stupid way you've been doing it until now. Those new More Important People will in turn bring their own More Important People, typically pulled in from their own past allies and partners, and so on.

Is such growth transformative? You bet. Does it have the potential for great success? Sure. But the process of Embiggening an already-successful small or midsized company is much, much more perilous than most executive teams imagine it to be, because even if got one of the rare teams that understands how to refurbish a Cessna into a 737 while it's in flight, never once letting it touch the ground, you're either going to get to your destination or you're going to hit that ground very, very hard.

It's also a very short walk from let's expand the company by bringing in executives who don't know all that much about our particular market niche but who can tell us how the bigger companies do things to the Musk Principle:

One Idiot Can Ruin Everything.

Let's assume, for the moment, that we have a theoretical company that's not run by barely-sentient human spambots like CNET's former owners or by the money-hoovering but let's-say well-meaning brunchlords that appear to have run Vice into the ground. What would growth look like in an ideal company?

Let's say we have a not-quite-startup, not-quite-established tech company, maybe it's got an operating budget somewhere in the $10 or $20 or $50 million range but it's got something special to it that, at least in the moment in question, is letting it make money hand over fist so there's good profits and what appear to be some real opportunities for growth. Maybe it's created a new bit of software that's taking off, or maybe it's designed a new handheld bit of electronics that lets you send someone else in the world a mild electric shock just by thinking bad thoughts about them—you know, something "useful." This is the sort of company that the world is full of, quiet and unassuming little nooks of industry that do alright for themselves and at some point think to themselves, but we could do better.

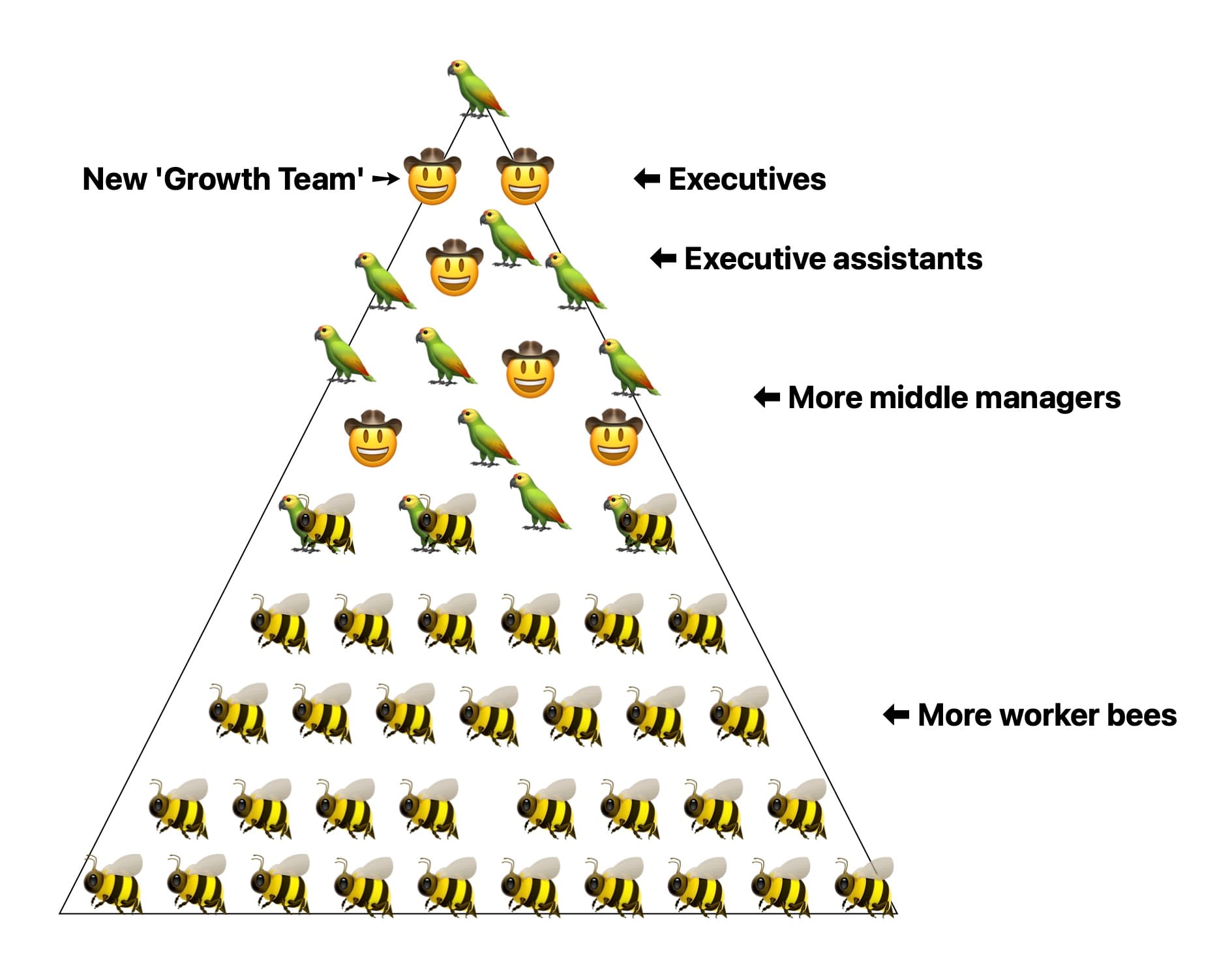

The organizational structure of our imaginary company generally gets depicted as something like this, though we'll forgo the lines representing who reports to who and prevent the vaguer version:

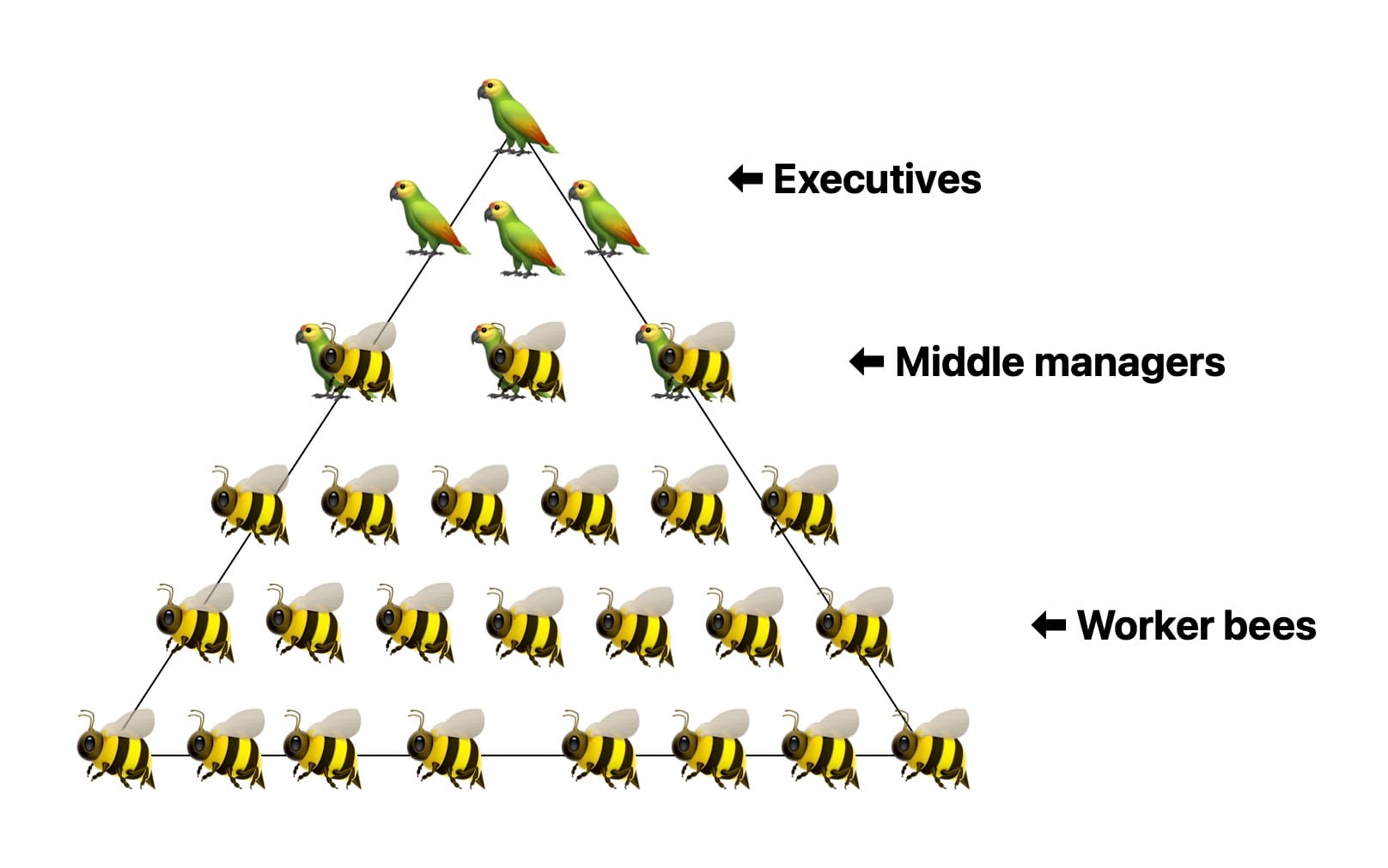

Good ol' boring triangle—nothing beats that. Hang on, for the purposes of discussion let's change those icons out to differentiate between roles a bit.

Now, if this were a glossy-cover book about management being displayed in an airport bookstore the author would probably make a very big deal of this hastily thrown-together picture. "There are two kinds of people in your organization," they would write. "There are birds, and there are bees. The birds are good at communicating and conversation, and the bees are good at bee-ing industrious but often do not communicate using words the rest of us can understand. Also, they like living in honeycomb structures in which every cell looks exactly like the others, and—"

Yeah, we're gonna head that off right there. Our differentiation is between people whose primary duties are deciding what the company does next and people whose primary duties are getting those things actually done, which is coincidentally the way all of corporate America thinks of itself so who are we to argue. In practice, there are no 100% birds or 100% bees—each position consists of some fraction of both. In our corporate environments we are all complex and confusing hybrids of both birds and bees, horrible mutant creatures with seven wings and nine legs and compound eyes over a misshapen beak, something akin to that final evolution in The Fly, the Jeff Goldblum version, all moaning and keening at each other, begging for a quick and painless death.

There, put that on the back cover of your stupid management book. I dare you.

"In our corporate environments we are all complex and confusing hybrids of both birds and bees, horrible mutant creatures with seven wings and nine legs and compound eyes over a misshapen beak, something akin to that final evolution in The Fly, the Jeff Goldblum version, all moaning and keening at each other, begging for a quick and painless death." — Some Airport Book

But to get back to the actual structure here, our imaginary shockingly well-run company is probably headed up either by the inventors of whatever product our company is selling or those who partnered with the inventors at the very beginning; the rest of the staff consist of people who were likely brought on in twos and threes over the years as needs arose and capacity needed to be ramped up. By and large we know this group of people is mostly pretty competent at what they do and mostly pretty knowledgeable about the product their company is selling, its development, the troubles that arose when it was being designed or upgraded. We know that because the company's doing well for itself, which means the current staff is bringing in measurably more money than the company is paying back out, which is precisely why our fictitious company is now contemplating a much more ambitious growth spurt to begin with.

So after things look pretty stable and the company's key staff have looked at the numbers and decided that they could probably sell a lot of other product or services similar to the ones they're now selling, if they only had the capacity to do it, and someone says we need to grow this thing. Not because they're horrible greedy brunchlords, but because it makes good business sense. So that's what they do.

And how is that done, in modern capitalist America after about 50 years of inundation with new MBA programs that try to universalize management concepts by grinding them all up and presenting them as a cure-all soylent goo, and with fawning "business" cable television networks interviewing top business leaders who may or may not secretly be amazing screw-ups who can't work the office coffee machine without three assistants and an exorcist, and with airport bookstores filled with ghostwritten management books with some billionaire executive's smug face on the cover? By and large the small-company executives will always arrive at the conclusion the books and magazines tell them they should: We need to hire experts who have worked at big companies, so they can teach us how big companies do things. Then we will become a big company.

And thus the fuse is lit.

Because there's no point in hiring Big Company People to turn you into a Big Company unless they're given the power to do it, the new hires are generally slotted in at very high-level positions and given quite a bit of deference when they Bigsplain how to do things. That's not nefarious, it's a perfectly sound management decision—and for those of you who are already screaming that it most certainly is not, shhhhh. We're getting to that.

So now we begin the transformation into a Bigger Company. The company begins to spend considerably more money on poking for new avenues of growth, and is willing to lose a large chunk of the company nest egg to find and capitalize on one. Internally, a restructuring begins to teach the managers and employees of this already successful company how things work at the bigger companies the new managers previously worked at, and the answer is invariably and always that the company needs to bring in more process, because that is what larger companies need to have to manage their 10,000 employees. It's simply a business fact: If you want to someday have 10,000 employees instead of 30 or 50 then it's quite obvious you need to start doing it too. Got an Excel spreadsheet for this or that management task? Consider the big-company approach of purchasing a new middleware platform to do it instead. Still using off-the-shelf accounting software? Oh you poor thing, big businesses have discovered numbers you've never even heard of.

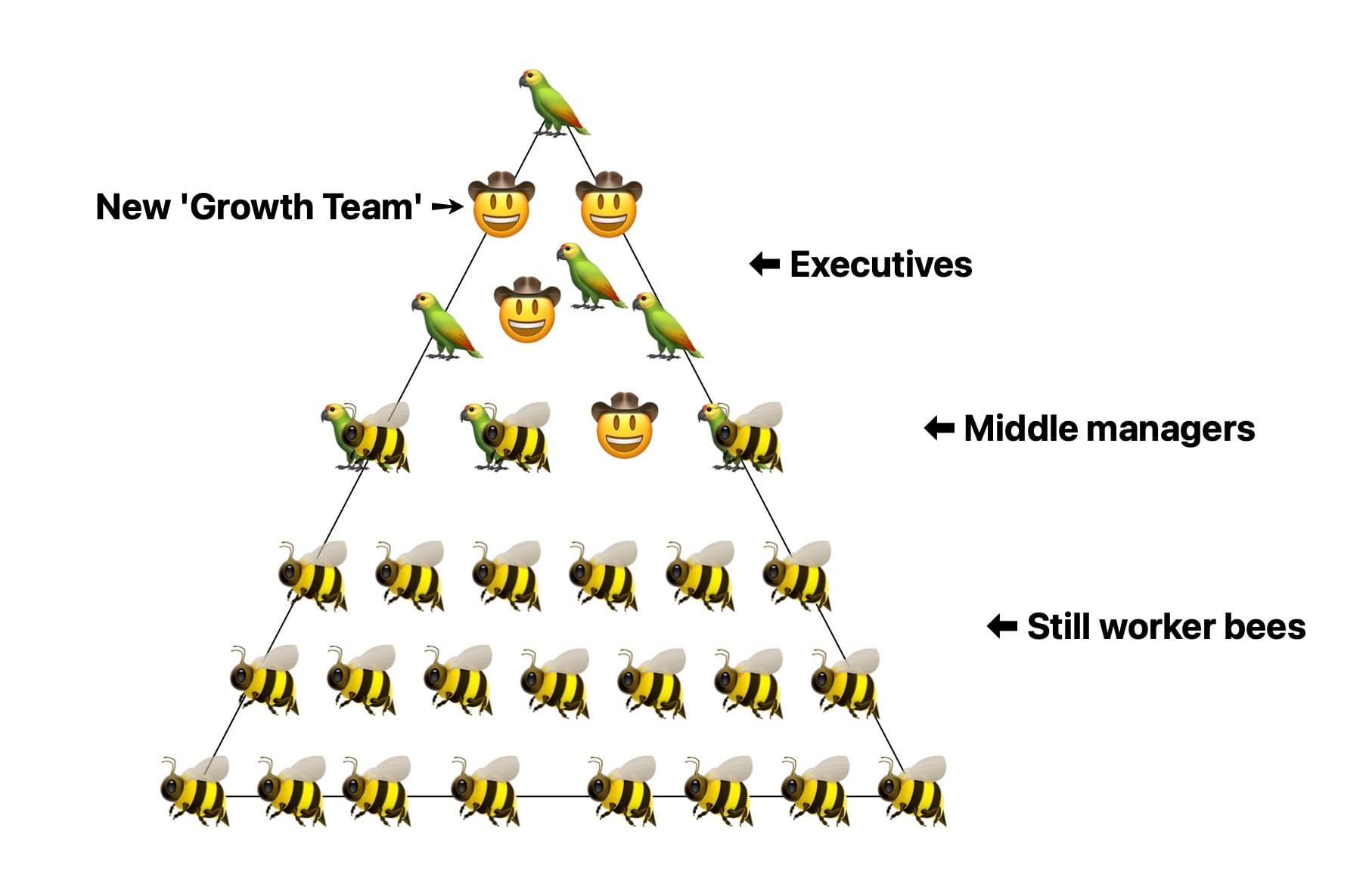

And because everyone here is smart, except for maybe Steve over there who does God knows what all day but is friends with one of the executives so nobody is even allowed to ask too loudly, everything goes great. The company hires more worker bees, and pushes into their new identified market niches, and because there's a heck of a lot more process in the big-company way of doing things the executive team needs to hire assistants to attend to it all, and one of the other rules of having a big company is that you need to have meetings, you need to have so many meetings, because how are you going to decide what the business should do next without meetings, so each executive may need another assistant or two to do the actual job they themselves were originally hired for, now that they themselves have to spend 20 hours a week just going to each other's meetings.

So now we're set up for rapid growth, or we will be if we just keep hiring Growth-Focused team managers and the human scaffolding they need to do their Growth jobs. It's a little unclear which person has which job duties up there at the top, but eh, that's the way things are done in these modern times when you're being growth-y and creating synergy and whatnot.

Nobody's being evil here. Nobody's swindling the company, or taking long lunches, or scheduling new regular all-hands department meetings all the bloody time because they're preening gobshites who would wither and die if they weren't allowed to give insufferable 20-minute monologues to a captive audience at least twice a week. No backstabbing, no flurries of HR complaints, and no intentional sabotage of one department in order to make another one look better—none of that petty real-world nonsense. Everyone's doing precisely what the Big Business manual says they ought to be doing to run a Big Business, and they're doing it competently and well. The company keeps looking for those new markets, and maybe even finds a few, and then ...

... something happens.

We all know how the economy works. There are booms, and there are busts. A sudden collapse of some other business sector that has absolutely nothing to do with yours can do widespread damage to every other sector of the economy and there's nothing you, in your own company, can do about it.

A collapse of some related business sector that you've come to depend on, though; now that can get existential very, very quickly.

If you're a company like Vice, or Twitter, or Tesla or Boeing or Oracle or any other you can name, there are a heck of a lot of market externalities you can't control. What if online advertising revenue collapsed, and the majority of your whole business just happens to have depended on ad revenue? What if it crashed by a whopping 90%, possibly but not necessarily due to the near-entirety of the business world finally realizing, oops, that Google's advertising products were veering ever-closer to becoming outright scams? If you're a company anything like Vice, you're going to be well and truly boned.

Even the best-run company on the planet will find that sort of market downturn to be an existential crisis. For a company attempting a managed growth spurt at the time, spending down its nest egg or racking up new debt while stuffing itself with all the bells and whistles of Big Company management because that's what's needed to "manifest" success later on, according to a bunch of preening gobshites who now live exclusively inside their ghostwritten airport bookstore management books, it means almost certain death. To repeat: Once a company starts that deficit-driven growth spurt, no matter what happens next, only a handful of them will succeed in reversing the process if things go bad. It's just not possible. There's no airport books on how to turn your big company into a smaller one, and the few that pretend at it are written by Big Company authors whose own bragged-about approach turns out to be, on closer examination, "and then I won the lottery, which does too count as a strategy."

Once a company starts that deficit-driven growth spurt, no matter what happens next, only a handful of them will succeed in reversing the process if things go bad. There are no management books that tell you how to shrink a large company into a smaller one.

The moment a company becomes successful enough to attempt a spurt of rapid, order-of-magnitude sized growth into new markets that may or may not be there—whether it be a self-funded attempt, a venture-funded attempt, or being purchased outright by a Big Company that wants to make it a new Big Company division, it lights a fuse. The company either makes it big, or they collapse under the weight of what they've become.

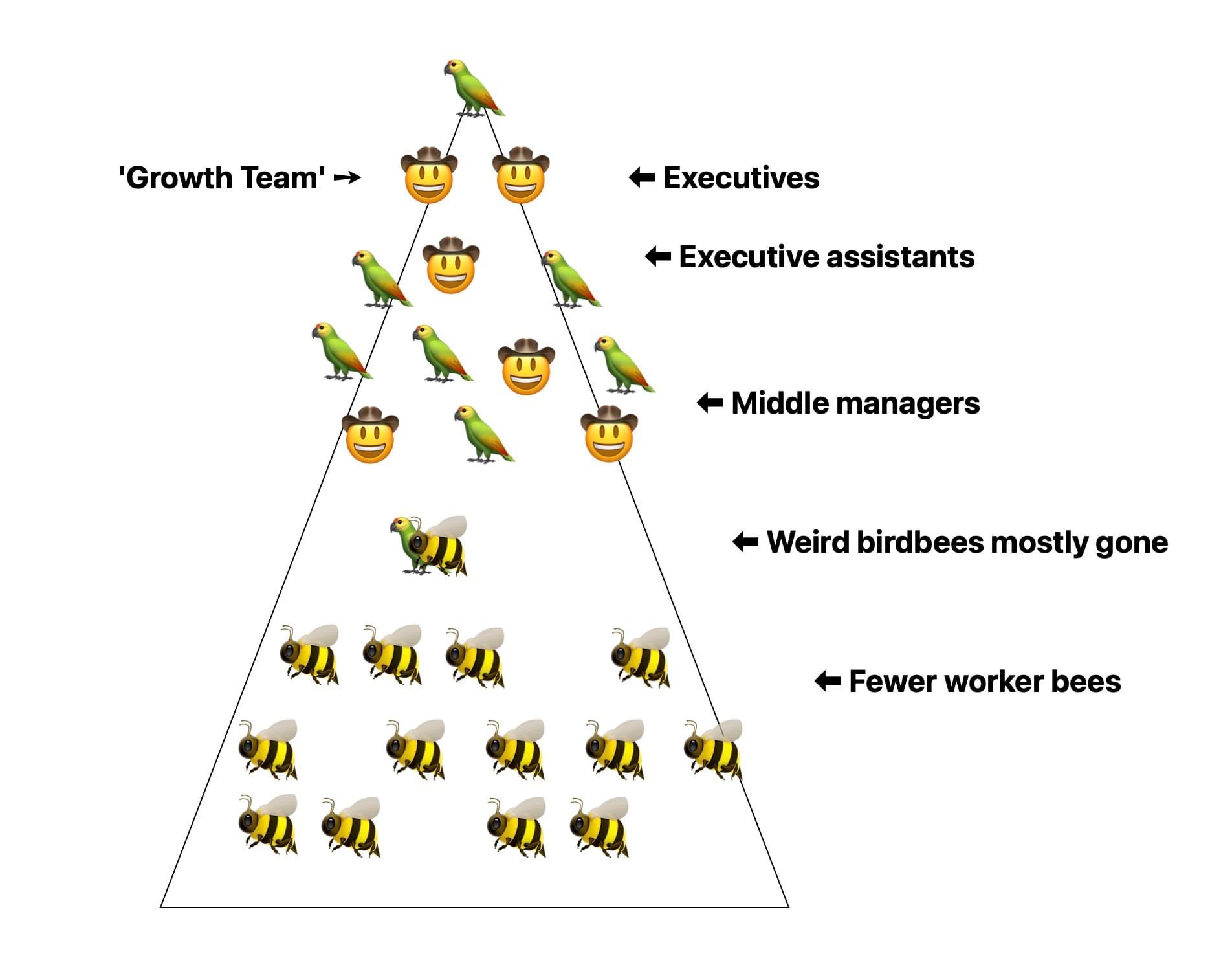

Let's look at how our theoretical well-run and growing company is most likely to respond to this new crisis. Well, thoughts of rapid expansion are probably done for, so the experimental forays into markets that might not even exist are put on hold. Costs need to be cut much more than that, though, and that generally means layoffs. We can't lay off the senior staff because then there'd be nobody around to Save The Company at the time it most needs saving, and their assistants aren't going to be cut because the executive team's workload is if anything going to rise the more dire the company's fortunes fall. Can't have that.

The company invariably decides that the majority of the layoffs need to come from much lower down in the company than that, so here we go. It's time to "trim the fat," the executives announce. All those new worker bee positions have to go, and since we're still losing money even after that we're going to need to get rid of even more people.

Whether you call it the brunchlord class or just Doing The Executive-Approved Executive Thing, a company flipping from Growth Mode to Survival Mode, Growth Team Version Of, will always end up looking like this:

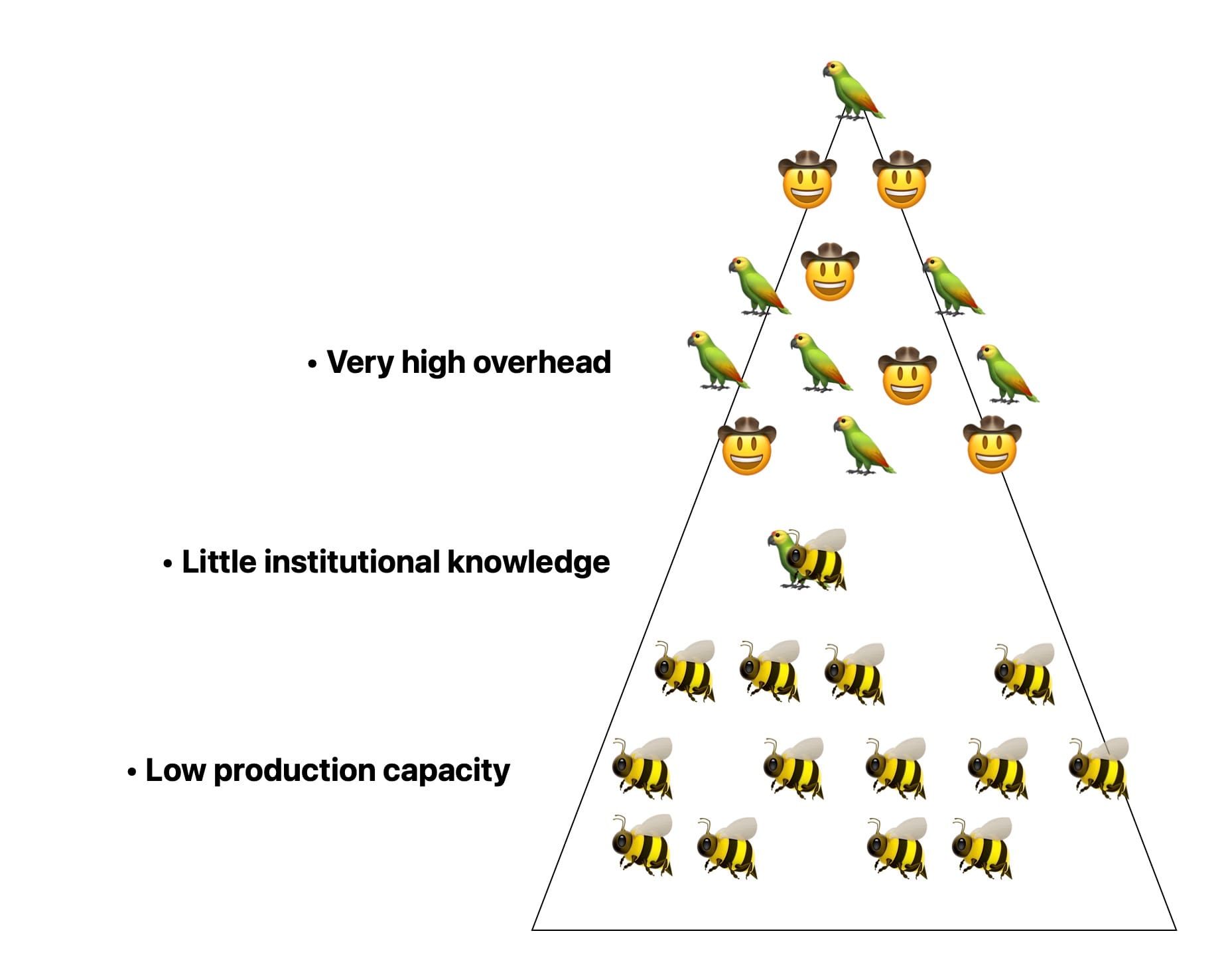

We've now got a much leaner-looking company than it was at the height of its expansion attempts, but it doesn't look much like the old version. It's going to retain that big-company shape, at the top, because everyone hired on during the growth spurt has been drilled on Big Company management styles and doesn't have the foggiest idea how they would get anything done otherwise. Compared to the company that was making enormous profits on their previous $10 or $20 or $50 million yearly budgets, this version has a whole lot of problems.

• Overhead is now enormous. None of those Big Company people come cheap, and the executive ranks as a whole have ballooned tremendously from the company's more smaller, more profitable times.

• Production capabilities, on the other hand, have tanked. There are fewer workers to produce the company's product, to market it, to sell it, and to provide customer support. These aren't things that can be automated, and unless you're the sort of brickheads who turned CNET into a robot vomitorium you're not likely to be dim enough to try.

• The company may have shrunk but the commitment to Big Company Process is sacrosanct, and that means the process of creating or iterating on company products significantly more expensive—and, more importantly, much less nimble. Nothing we can do about that either, says the new executive team. Our hands are tied.

• And as for those previous teams that once allowed the company to make big profits with far fewer workers: They don't exist anymore, and they're not coming back. The company got rid of them to staff up new versions headed by new managers who collect larger paychecks but know little to nothing about where those previous efficiencies came from and, because this is what every would-be executive is taught in their MBA programs or by their Big Company mentors, they most emphatically do not care. MBA programs are premised on the notion that "management" is a generic concept that can be applied to any company or department with no prior knowledge of what any of your new underlings actually might do all day, and all of modern corporate culture in fact relies on the premise for its musical chairs-version of Doing Management that sends executives hopscotching from company to company in short bursts, each time with more "qualifications" that require higher pay at their new growth-oriented company.

Put it all together and the competitive advantage that boosted the company's fortunes has now been completely scrubbed out. The teams that brought to the company to success were likely disbanded, and if they're not they're buried under too many new layers of management to ever be able to be granted authority to do what they did the first time. The company might well be able to still sell as many widgets or, in the case of Vice, produce as many articles as before, but with all the new overhead the profit margins have dropped and may even have dipped below zero.

A company that once thought itself primed for rapid growth off $20 or $50 million in yearly sales may now have dipped back to that same $20 or $50 million income range—but now instead of being able to tuck away good profits at that income, now it's unsustainable.

Yeah, that company's dead. It may sputter along, with executives telling all who listen that well this is a rough patch but our remaining skeleton crew will get through it, but it's done. You can't run a small company off those same Big Company methods, and there's not one Big Company-trained executive who's going to figure that out even as the bank account drains to zero. The last thing that happens is a memo to remaining staffers that says something like:

As all of you know, our company has been severely impacted by changing market conditions. While our executive team tried all possible methods of returning to profitability, those market conditions have continued to be severe and the team has decided there are no further options available. It is a crying damn shame that these severe and changing market conditions unexpectedly came in to shatter our team's grand and perfect vision, but that's business. You have three hours to clean out your desks.

The executive team then holds one last executive pity party, decides how much of the company bank account needs to be diverted to paying them each a bit of going-away money to make up for all the emotional trauma they endured trying to save the ungrateful buzzing worker bees, and now their resumes have a new line that says something like empowered workers and reorganized corporate structures to respond to changing market conditions and off they go.

Nobody did anything untoward. There were no long lunches. They got paid what the industry says important Big Company people ought to get paid, and nobody considers those salaries outlandish—at least, nobody among those who have any say in setting those numbers. In our fictional company, nobody intentionally tried to siphon away every last cent of company money while destroying the company's means of survival; they just did what the books told them to do. When it didn't work they did it a few more times to make good and sure.

The Growth Bomb went off, and now the company is just another bit of rubble cluttering up the industry landscape.

This isn't just a sad story for the sake of sad stories; we can learn a lot from our fictional example. Unlike our Vice Media example, our invented case isn't tainted by questions of whether the executive team made decisions that hemorrhaged money or whether someone bought a new boat as company coffers went dry. The point, instead, is that once a company charts a path to growth that significantly and suddenly expands its staff in order to capture new Big Business status, a fuse is lit on a bomb that will go off no matter what happens next. Either the company succeeds in finding its new windfall—or it bloats itself into irrelevance and collapses before it happens.

Making matters worse, in our new business world in which nobody is expected to know anything about the delicate internals of a company before popping in and Managing The Hell Outta It, the odds of this team of newcomers finding a golden goose that the smaller but very successful previous team didn't think of after many years in the business are very close to zero. The odds of management being able to go back to the old status quo if things go wrong are at absolute zero, and we're talking zero degrees Kelvin here not any of this Fahrenheit or Celsius nonsense.

All those stories you hear about the founders of some company closing up shop and starting a new company from scratch? It isn't because those founders got bored. It's because it's easier to create a whole new company with lean teams and small-company agility than to convince the executives at their collapsing last company that they needed to winnow their own ranks, abandon now-pointless process bloat, and go back to the formulas that made their now-struggling company successful the first time around.

As for the lessons to be learned from the fall of Vice and the fall of innumerable hedge fund-purchased or venture capital-captured profitable firms before or since, the biggest of all is that fatal flaw we brushed up against in the beginning:

By and large the small-company executives will always arrive at the same conclusion: We need to hire people who have worked at big companies, so they can teach us how big companies do things. Then we will become a big company.

Yeah, that is not how that works. Oh, it might work, but it's putting the cart well before the horse. That cart is about three miles down the road and nobody's so much as even tacked up the horse yet. Adopting big business process before you need it is just overhead, and overhead is the thing that all those MBA programs were insisting be trimmed to the bone because it was bad, bad, kill-your-mother bad whenever anybody but you insisted on doing it, but when you do it suddenly it's the magic elixir that will make your employees poop unicorns.

• Processes designed for 100 workers are ridiculous when adopted by 10-person teams. The whole point of the large-company processes is to standardize and generify a hundred people's worth of tasks into scannable bullet-point-like lists for department managers to have any hope of being able to see the whole from the parts. But all processes are by definition overhead, and processes that don't accomplish anything are called makework. I couldn't tell you why, precisely, a sizable percentage of all MBAs spend their time boasting about how much makework they're able to create. I definitely couldn't tell you why the ability to slow progress to a crawl compared to how the company's smaller teams functioned somehow translates into expertise the previous team didn't have, but anyone coming from a Big Company environment is usually very insistent on that point..

• The very premise of hiring "Big Company" managers to learn how to become a Big Company is flawed from the outset. When companies look to hire on managers who can "grow the company to the next stage," they aren't hiring the corporate managers who grew the Big Companies to that size. Those people are few and far between and your small-sized company likely can't come anywhere close to being able to afford them. Instead, the executive teams found to "grow" the company aren't people with experience growing companies, but people who merely have Existed at those big companies. They weren't there when the processes they used were put in place. They don't know why those plans were instituted, or what flaws the old systems had. They were told to do it This Way and so from then on, like any manager worth their salt, they will forever tell everyone they work with that This Way was the way to do things and all the other ways are stupid and unprofessional and the sort of stuff primitive hillfolk would do between cave-painting sessions. How did your company get anywhere without doing it This Way? How did you manage to find all these employees who never thought to do it This Way? Well things have got to change around here, that's for darn sure.

Next hint:

Because there's no point in hiring Big Company People to turn you into a Big Company unless they're given the power to do it, the new hires are generally put in high-level positions and given quite a bit of deference when they Bigsplain how to do things.

Is that how it should be done? Why?

No, really. Why? It's a legitimate question, but one that many companies never think to ask.

On the one hand your smallish company is already successful, with good profit margins and a staff that likely spent years polishing their own processes to smooth out the rough edges of your particular industry's needs. In the process they've gained institutional knowledge that has boosted your company over your rivals; whatever you're doing, it's clear you're doing it well.

On the other hand, your company now has the opportunity to hire new, more expensive executives and managers who likely know not a damn thing about your specific business niche and who instead bring to the table the Big Company pantomimes that are supposedly so universal that your company will achieve new and better successes just by adopting them.

If you really intend for your company to survive even if your new growth spurt doesn't pan out, which of those two groups ought to be put in charge of which?

There you go. That was the second disastrous mistake. And again: It's not one a company can come back from.

There's two major ways to grow a tech company; you can either do it by Team Expansion, which takes the existing teams and blends in new assistants and processes that help your team leaders determine which processes need to be tightened up and which, for your particular industry, amount to pointless hokum. Or you can do it through Team Replacement, in which you overtop each of your currently successful managers with new, less knowledgable hires who then reorganize their new teams according to the Dungeon Master's Big Book Of Business Rules And Hokum, stripping all decision-making authority from your previously successful teams and substituting their own.

Hedge funds and venture capitalists generally insist on the Dungeon Master role-play approach because they're promising to dump tens or hundreds of millions of dollars into the company and they're going to want to be damn sure that your company is following the instructions they want you to follow—but it's a destructive process. Once it takes place, there are no old teams to reconstitute if things go bad, so it's an all-or-nothing bet.

Unless they're in a dreadful hurry, private companies tend to instead prefer expansion of their existing teams, which is almost always a much slower process because it's iterative instead of destructive. That's how a company with $1 million in annual revenue gets to the $20 million point to begin with. It's safer. It's at least partially reversible. It can be tweaked according to each iteration's results.

If you're in charge of a privately held company and you instead attempt the all-or-nothing Dungeon Master toss-the-teams-out method without someone bribing you into it to the tune of a few hundred million dollars, I don't even know what to tell you. That's like agreeing to nail your tongue to the conference room table in exchange for a now-empty box of Thin Mints.

If we ask ourselves what Vice could have done better, the only real answer is DGB: Don't Get Bought. Once a set of benefactors-slash-overlords decided that they were going to make Vice the biggest name in media, the game became raising money and then spending that money. Whatever once made individual pieces of Vice successful was always going to be ignored in favor of the plan of "we're going to buy a truly gluttonous number of lottery tickets and count on at least one of these babies paying off." The Growth-At-All-Costs fuse was lit and the bomb went off, and then it was repeated several more times for good measure; the outcome was the same story that's become commonplace across all of tech-focused media these days.

The company crashed, and those in the once-successful bits of the company who had the wherewithal to do it abandoned ship to form their own new versions that—you guessed it—did away with all the new layers of gutpunchingly expensive management to focus instead on steady, sustainable incomes for the people doing the actual work. That was also the rescue plan for the similarly overburdened Onion, which was left for dead by G/O Media and revived with a bare-bones executive team organized by former NBC News reporter Ben Collins.

It's that drive for exponential profits that set the bombs now going off over all of media, and that, dear readers, is why journalism, opinion writing, and every other form of serial writing is now moving to one-author or several-author subscription-based websites. Every company is suffering the same damage and is in fire-the-workers mode as their Growth Teams try to figure out what to do with their bloated executive structures, wiped-out institutional advantages and Steve, who apparently will never be fired even though right now he's given up on drawing his mysterious charts and is just openly playing with Legos in the office.

If there's any good news for online media during the industry's near-total collapse, and it's really stretching things to say so, it's that hedge funders and other get-richer-quick, gambling-obsessed wealth groups may be getting tired of setting their money on fire in the hopes that the smoke will summon the grand and fickle spirit of The Next Big Thing. They've moved on from media and are lighting even larger piles of money on fire trying to teach vast banks of computer hardware to write poetry, under the dead certainty that if they can get an acre of silicon to write poetry that this will somehow be worth All The Money.

As for why all of these industries and companies are being full-on attacked by spin-the-wheel private equity groups obsessed over finding that next big thing no matter how many companies they have buy and kill off to do it, one good summary can be found at Apperceptive. The short version is that private equity became addicted after two big tech success stories netted lottery-sized jackpots, and they've been chasing that same high of supposed "exponential growth" ever since. The problem with that approach is that the markets have changed, and the odds of repeating those successes are now vanishingly low.

Software is eating the world," proposed Marc Andreessen, who had parlayed his brief time building the first graphical web browser into a career as a sage among a set of people overwhelmingly convinced of their own importance. Endless treatises were written on how transformative new business strategies had allowed for—would continue to allow for—this kind of transformation. VCs invested in companies based on what they described as the "hockey stick" growth curve. They were looking for businesses where scale and revenue would hit an inflection point where they would start to grow something close to exponentially, vastly outstripping the underlying costs. They wanted this because they had had it before, because they had come to believe it was not merely their due, but something close to the ineluctable purpose.

[...] The same dynamic is at play when private equity—or large conglomerates behaving like private equity in acquisitions—buy newspapers or websites on the premise that they will achieve vast and cost-less achievments in efficiency, whether by replacing writers with AI or some other more-or-less implausible snake oil. It might not work, indeed it probably won't work, but history tells them that the payoff if it does work is so extravagant that the risk, to them, seems perfectly worth it.

What we have in the tech and media markets right now are irrational investment patterns that amount to a string of all-or-nothing bets, one by one by one, to snap up companies, shovel money into "growth," and then shutter them entirely when the bet doesn't pay off. It's compulsive gambling, nothing more, but compulsive gamblers have written an unending stream of books about how their scant few wins prove that they've got a system that can overcome the odds and pay off, just you watch. It's a truly insane way to run entire industries, but here we are. Attempting to regulate these same bozos is what earned the Biden administration widespread techbro ire, because after those first wild successes all of Silicon Valley was rewired as a gambling den for rich misanthropes. Pivot to Video; Crypto Everything; Poetry By Robot; you name it, the same eternally weird private island owners have flocked to it and insisted that you, you chump, are the mean one for not believing in them.

Want to kill your tech company? Want to kill your media company? Want to kill your media company that's also a tech company? Take a successful business model, pluck it out from the hands of the managers and employees who built up the institutional knowledge that's given you that special something that none of your competitors could quite duplicate, and hand it over to a new, larger, and much more expensive executive team that doesn't know your business, neither knows nor cares what your product actually is or what niche it's aimed at, but is simultaneously very, very sure that they can turn your company into the next industry giant just by pantomiming whatever the hell the geniuses over at Boeing were doing right before parts of their planes started falling off.

Yeah, that'll do it all right. There's no coming back from that.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.