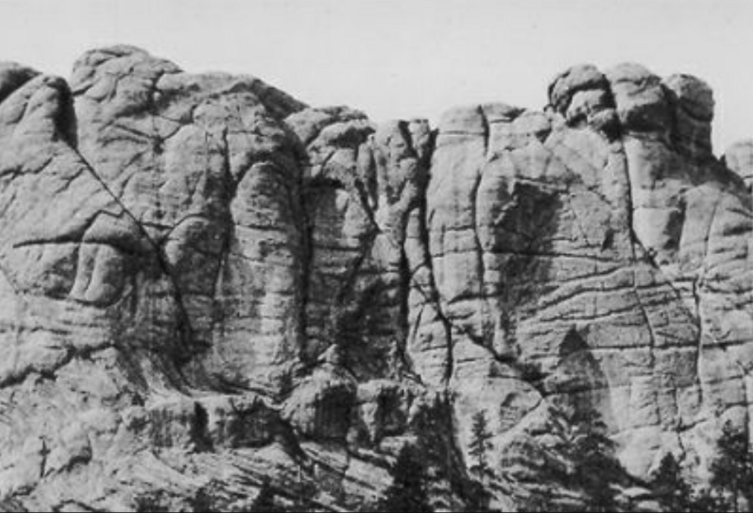

If you have even a passing familiarity with America's space program and likely even if you haven't, you may be aware of a theoretical phenomenon dubbed Kessler syndrome. In the late 1970's, NASA scientist Donald Kessler published modeling results that suggested that the rapid accumulation of manmade debris in low Earth orbit, the product of just a few decade's worth of humanity's first explorations into space, was likely more dangerous than world space programs had been presuming it to be. His models implied that repeated orbital collisions between those old bits of space debris, whether large defunct satellites or small but high-speed microfragments produced by previous satellite collisions or by explosions in low Earth orbit, would result in the production of more but smaller fragments, which would then themselves collide to create still more debris.

The consequences of this expanding cloud of debris would be severe. New satellites launched into orbit would be able to operate only for briefer and briefer periods of time before becoming so damaged by particle collisions that they could not function; those satellites would then themselves fragment over time, making the problem exponentially worse yet again. Eventually low Earth orbit would become so littered with such fragments as to make launches of new satellites or manned missions impracticably dangerous, and mankind would be cut off from those orbits for however many centuries or millennia it took for that manmade micrometeoroid belt to eventually deorbit and fall back to Earth.

Kessler's modeling was especially notable because it suggested that the chain of events would take only decades to manifest, and his predictions have already appeared to have proven true; debris strikes and near-misses on satellites and manned spacecraft are becoming increasingly common, with spacecraft not-infrequently having to maneuver in orbit solely for the purpose of dodging some especially dangerous bit of space junk. The debris cascade is already well underway, and with it the possibility that the orbits we now shove most of our satellites into will become effectively unusable within our lifetimes.

There has been a great deal of attention paid to the now-rapid degradation of the internet for the very tasks that it once excelled at. Email is now primarily a garbage dump of spammers and malware; Google's mighty search engine is visibly degrading before our very eyes, as it becomes buried under the weight of uncountably many fraudulent or bot-created supposed results; Facebook and similar social media networks are increasingly frustrating user attempts to connect to the friends they wanted to connect to while flooding user feeds with similar advertising, bots, and disinformation. There was a brief window of time in which Amazon, with its willingness to prioritize products by user reviews, might have become a potential salve warding off the worst of consumerism's rampant scams and flimflammery, but the joke was on us; Amazon now appears too focused on capturing the revenue from innumerable dubiously-branded gray market imports, and companies can dodge poor reviews for their products by using the time-worn tactics of traveling snake oil salesmen: Pack your bags, get out of town, and reappear one town over under a newly assumed name and with a new label on the bottles.

It was Corey Doctorow that coined the now-widespread term for this internet platform phenomenon: enshittification, a "seemingly inevitable consequence" of the power gained by any middleware platform that grows to a dominant market position.

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

I call this enshittification, and it is a seemingly inevitable consequence arising from the combination of the ease of changing how a platform allocates value, combined with the nature of a "two sided market," where a platform sits between buyers and sellers, holding each hostage to the other, raking off an ever-larger share of the value that passes between them.

That is a very good descriptor of the trends that are causing Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other current market giants to chew off their own feet. Using market dominance to abuse your once-loyal customers until they turn on you is historically responsible for the fall of a great many other colossi long before the internet ever made the scene; it's why the Fourth of July is a national holiday.

The worsening of the internet as knowledge source an be attributed to one specific phenomenon: the exponential production of informational "debris."

I've never seen the wider, technology-encompassing phenomenon packaged up under a satisfactory name, however. It's not just the biggest companies struggling, or certain market sectors. The internet in its entirety is getting much, much worse at all the things that once made it revolutionary, and it all can be attributed to one specific phenomenon: the exponential production of informational "debris." The production of malicious, exploitative, or propagandistic content is growing even as the production of factual, informational, and objective content continues to shrink—and there seems no plausible mechanism for reversing course on either front.

Consider the following trends:

The rapid growth of manipulative information sources that present themselves as objective but are fronts for manipulating public opinion. The most notorious may be the fake news sites apparently run by or for Russian intelligence services, sites with names such as "The Houston Post" that spread misinformation seemingly designed to undermine support for the Ukrainian government or create distrust in American elections. Earlier this year it was revealed that Israeli government backed an artificial information campaign targeting U.S. lawmakers, one in which "around 600 fake profiles unleashed more than 2,000 coordinated comments per week" supporting support for the Israeli military's brutal actions in Gaza, including ones "dismissing claims of human rights abuses." American political groups are themselves turning to so-called "pink slime" campaigns producing misleading websites designed to look like true news organizations but which instead publish "reports" that target political opponents.

Ever-expanding efforts by "good" information sources to monetize information by presenting it in smaller and smaller visual frames that are surrounded by more and more visual "debris"—advertising content the user did not ask for or alternative "information" that better matches what the host would prefer users see. One example would be Amazon's intentional enshittification, flooding product pages with sponsored and often dubiously branded alternatives. Non-middleware content creators, however, are have been expanding their use of such "debris" as a survival strategy. Go to most major news network's or newspaper's online sites and you will be assaulted with advertisement "debris" to an extent that threatens to overwhelm the content you came to see. As advertising rates continue to decline, content providers have expanded the number of advertising slots and loosened guidelines on what companies can place in them—likely kicking off a self-defeating cycle that will see both those trends continue.

The continuing, user-predatory degradation of internet advertising itself. Once used for the brand and product awareness campaigns that typify offline advertising efforts, the internet version is becoming dominated by ad-slot matryoshka: misleading, often sensationalized advertisements that coax users to visit a new site that can bombard them with a larger number of even lower-quality advertisements stuffed beside misinformation or bot-generated "content." Clicking these ads repeats the cycle; the cycle appears to always end, sooner or later, in a malware link.

The explosion of "Artificial Intelligence"-created campaigns purpose-built to guide users to those misleading, manipulative, or matryoshka sites. While A.I. engineers have for decades boasted of all the potential uses for the technology once it has evolved, what we are seeing in current large language models is that they are primarily useful as tools of deception. Hoards of cheaply produced, A.I.-generated sites are now scattered through Google search results, each seemingly designed to either artificially boost the presence of a presumably-paying client or, more commonly, as "payloads" directing users to ad-fueled matryoshka sites.

We're seeing the makings of one particular "A.I." trend that's worth calling out explicitly: the use of A.I. to suck up the knowledge of expertise-based websites, sites with large collections of "how-to" content or other problem-solving resources, and eject it out again as a "new" site that represents that knowledge as of their own creation. It is so cheap a business plan as to be almost free; the purpose, again, seems most often to be to create a base on which advertising or malware matryoshka can be assembled.

Outright theft and repackaging of works, usually for deceptive if not criminal purposes. A typifying example is Spencer Ackerman's story of discovering past articles he had written being passed off as new content on a new seemingly partially AI-generated, partially theft-based "news" site that attributed each article not to him, but to human writers that don't appear to actually exist. (I expect many cases like this are the result of the still-barely-reported dark secret of the current "A.I" boom; a nontrivial chunk of it appears to be based not on the new language models themselves, but on the proliferation of global sweatshops in which cheap labor or rudimentary programming is used to simulate "A.I." results as part of some company's larger corporate scam. It requires no advanced technology to steal content from legitimate sources and assign randomly assigned "writers" and "biographies" to each piece; a simple shell script can do the same, and the whole thing could run on about as much processing power as a modern "smart" refrigerator.)

The rapid expansion of A.I. "false reality" capabilities, in which intentionally fraudulent, faked audio clips and visual footage are becoming not just possible, but increasingly inexpensive and increasingly indistinguishable from undoctored, real-world images and recordings.

The triple threat of now plausible-sounding computer generated written content, plausible computer generated multimedia content, and rapidly expanding server resources to produce both is likely to have severe impacts. Even before digitization, we have long relied on tells to evaluate whether a particular piece of media is real or faked. What happens when generated content becomes good enough to have none of those technical tells? No ready mechanism for establishing whether, say, John F. Kennedy and Elvis Presley did or did not once paddle a duck boat across Harlem Meer?

What happens when the technology to show any world political leader giving any speech a motivated fabulist dreams up becomes not just possible, but nearly free?

We all know what will happen. It's already happening. Furious battles arguing over which real-world events may not have really happened and which purely fraudulent versions are now supposedly true will rage, and for the most part such arguments will be unwinnable without the input of credible observers—journalists, for example—either present for the real events or in possession of additional information that refutes the false ones.

The current internet is so awash in false information as to have already crossed the line from net informer to net misinformer on certain narrow subjects.

Artificial footage is not necessary for conspiratorial information to take hold. Chain letters and pyramid schemes have long showed the relative triviality of convincing a networks of humans to believe untrue things, and the current internet is so awash in false information as to have already crossed the line from net informer to net misinformer on certain narrow subjects. But global interconnectivity has done what was impossible for previous generations of con artists, propagandists, and delusional cranks: It has allowed all of them unfettered access to an online everyone. Each individual fraud can be distributed to masses previously undreamt of—not for the cost even of printing and postage stamps, but nearly for free.

In parallel, trends for the production of true and valid information are almost uniformly negative:

Online and offline news-based and other content companies are shuttering their doors as both journalism and content creation in general proves a money-losing proposition. Much of this goes back to the collapse of advertising as a plausible revenue source: First the internet devoured longtime local newspaper cash sources like classified ads and local business advertising. Then, after those papers were forced to downsize, close, or move to online-only operations, Google and other middleware actors began monopolizing what little revenue was left. At some point so much value has been extracted that a plausible path forward no longer appears, and those old sources of news and information disappear.

Sites looking to maximize ad revenues are prioritizing content that is briefer and contains less information than previous versions. The moves are attributed to everything from supposedly shortening attention spans to the prevalence of mobile phones, but the end result is that users are being presented with less information; less nuance, less detail about motives and histories, fewer rebutting facts. Looking for factual information, as a responsible user, is increasingly resulting in less total information being found.

Factual information is increasingly being hidden behind paywalls. The natural recourse for content sources that can no longer support themselves with ad revenues is to move towards paywalled content. Scientific journals have long blocked public access from research with similar fees; it is an even more precarious development when it is the day-to-day news being bricked up and put behind public view.

These are not disparate trends, but a single trend. Creating factual content of any sort has associated costs. From scientific research to daily journalism, and from corruption investigations to breezy product or movie reviews, all of it has fixed costs that cannot easily or ethically be weaved around. Finding and publishing accurate information costs money.

The bigger picture, then, is this:

• The costs of discovering and publishing factual information continue to be fixed.

• The costs of distributing computer-automated, stolen, or fictional information are now also increasingly trending towards zero.

We can easily extrapolate from there:

• The production of factual information is likely to either remain steady or decline.

• Computer-automated false information sources will likely increase exponentially.

That, then, begins to look a great deal like the cascading "debris" problems modeled by Kessler to describe a scenario in which the proliferation of dangerous space junk results in a space so overwhelmed with such fragments as to make it unusable going forward. What happens when the "debris" of misinformation is so widespread as to make the retrieval of legitimate and useful information difficult to impossible?

The publicly accessible internet loses the vast majority of its current value, that's what happens. The largest and most accessible source of information in human history is buried in a debris field of auto-generated falsehoods, auto-tailored manipulations, and other detritus. And the amount of disinformation may not just be large, but exist in effectively uncountable permutations.

That right there is what Internet Kessler Syndrome could look like. The internet will still exist. But the graph of it, its design as a vast system of information-providing nodes connected by search engines and crosslinks, will be useless. Entering at any node will become exponentially more likely to deliver you to a subgraph of disinformation vendors; visiting your social networks will result in an assault of bizarrely premised hoaxes and fake assertions that are believed by a sizable fraction of users because they were directed to different nodes than you were.

You will walk away from each visit so pitted with debris as to be measurably less knowledgable than you started out. The globe-spanning entity known as the internet will exist, yes, but it will represent a fully fictional, mostly bot-generated world that both pretends to be our own and looks not a damn thing like it.

So, uh, yeah. Goodie, I suppose?

Now, there's a danger in presuming any trend to be permanent—that's how you end up with a closet full of white suits and dead goldfish in your shoes. But what's remarkable about this Internet Debris Cascade theory, or Digital Kessler Syndrome, or Moore's Law But For Enshittification or whatever you want to call it is that, at least with the systems that have been built to date, there seems to be no plausible counters that would result in a new, less-than-terrible equilibrium. Whatever scenario we might propose for why the exponential explosion of false information would eventually subside has considerably less actual evidence behind it than the evidence of cascade itself.

Are we to believe that A.I, in the form of the current large language models, will rapidly gain the ability to discern truth and discard fiction? That's extraordinarily unlikely. It's often a difficult job even for human fact checkers; to a machine that "learns" by playing extravagant word association games, the concept has no meaning. Nor is it likely that LLM companies will spring for the sort of aggressive, human-governed content training that would prune hallucinatory answers as fast as new applications of the technology started churning them out. That level of human expense would defeat the whole purpose of most online LLM usage.

Are we to believe that A.I. and pseudo-A.I. companies will begin better policing their clients so as to eliminate the sorts of intentional fraud that are now running rampant, such as prohibiting the output of "headshots" or "biographies" of fictional people? Not possible.

Are we to believe that the problems of rapidly growing hallucinatory A.I. content will be tempered because companies will refrain from training their products on the output of their products? No, that's an irrelevancy. The point of A.I. output is to be plausibly indistinguishable from human-generated content; even if each engine properly refrains from consuming prior versions of its own output, other LLMs will trawl for and incorporate those materials. This digital centipede will end up eating its own online waste whether companies intend it to happen or not.

And all of those emergency technology concerns rank at the bottom of the true problem of cascading disinformation. The larger concern is that the internet as currently built is almost custom-designed for intentional distribution of misinformation and disinformation. We saw the problem begin to consume both social media sites and global search results long before LLMs entered widespread use; all new technology has done is better automate the process, allowing such disinformation to be distributed even more rapidly and at even lower cost.

If information requires resources to create and disinformation requires none, that's the ballgame.

If information requires resources to create and disinformation requires none, that's the ballgame. Disinformation used to have more substantial costs behind it, whether it be the cost of printing, the costs of mailing, or the costs of renting television time. All of those have gone away in the internet age. The irregularity of predicting which disinformation campaigns or money-stealing scams will be the most profitable is no longer a burden; automation allows innumerable versions to be produced and tested at the same time.

For legitimate content providers, the experience is increasingly one of displaying their art in a crowded exhibition hall, only for nearby exhibitors to respond by dropping tens of thousands of live roaches into the building from crates that they had hoisted into the rafters. At some point skill and intent become irrelevant: Which of the two exhibits do you think will seize the attention of the visiting crowds?

What's the way out? You've got me. I don't know how you solve a problem of exponential levels of artificial, non-human-produced "debris" crowding out any forum that allows public participation at all, or how search companies could effectively clip out such "debris" nodes from their own graphs—or, in fact, how to convince them they might want to. "I'm not a robot" checkboxes get you only so far.

All possible solutions appear to involve human intervention—the exact expense that search-oriented companies, social media companies, and generative A.I. products seek to minimize. It might even be a tragedy of the commons—styled problem, in that in companies looking to ignore their content responsibilities when it comes to forum moderation, information ranking and evaluation, and information production are all quite happy to dump all of the resulting debris into the public square and will, just like their polluting real-world counterparts, shift the cleanup costs to the general public.

But again we run into the exponential catch: If a site claiming to be that of an NBC affiliate in Winslow, California gets flagged for removal by human cleaners because there's no town named Winslow in the state, much less one large enough for an NBC affiliate, the removal hardly matters because legions of automated systems will already have made another ten such sites in the time it took for the human cleaner to remove the first.

If anything, the "solution" might be a return of the internet to the days of ... America Online. No, I'm not even kidding on this one.

If the graph of the public internet is being willingly contaminated by global groups of bad or merely indifferent actors, such that Information itself can no longer financially or discoverably exist in the debris field of intentional matryoshka-premised Misinformation surrounding it, the only sustainable solution is the removal of the ability to add misinformational nodes to the internet at all. To in effect ignore newly produced content, and instead turn to competing systems in which the "internet" is made up of competing subgraphs that contain only curated, vetted sites that have passed some as-of-yet-abstract quality bar.

Human-curated sub-internets with constrained abilities to pass content from one to another? That's an absolutely horrifying thought. It's the old America Online model, one in which a custom portal weeds out all the dark corners of the internet and presents a family-friendly but extraordinarily narrow subset. Or, in other words, we would abandon the orbit represented by the "global" information network and be forced instead into more expensive but less debris-filled ones.

The implications of such a system would be enormous. One can imagine a technology subnet that consists solely of StackOverflow—the self-curating site every current LLM scrapes its own technology problem-solving worksheets from. Another might exist solely of "recognized" news sources, a human-curated set of approved information outlets that new sites would have to jump through hoops to be included in. We can already see the dangers; curating companies would have vast powers to police "acceptable" content, and that would greatly strip one of the past internet's greatest assets: The ability for niche obsessions and power-challenging narratives to thrive without seeking or needing the approval of any such gatekeeper.

The biggest change would that truly global internet searches, of the sort that Google became a giant providing, might simply not exist (anyone who thinks this improbable need only go to the current version of Google; you cannot plausibly claim it is not already a shadow of what it once was.) There would be no crawlers sent out to index and catalog all of humanity's growing knowledge, because no crawler could productively operate in the orbital debris field generated by bots purpose-built to manipulate them. Google's past systems of assigning trust to nodes according to the trust assigned to nodes that reference them can't work in a system where node "authors", their commenters, and their references are all auto-engineered to mimic those patterns.

And it's not likely that human curators could tell the difference between, say, bot-generated product reviews and genuine ones. It's already hard to tell, and the problem is only going to get—here's that word again—exponentially worse.

I'm not going to pretend I can game out exactly how all of that would shake out. What I don't see, however, is an automated solution to an automated problem. There's no purely-online, purely-within-the-graph, and purely automated test for quality or legitimacy that can't be gamed and overcome by a collective automated response. That leaves only outside-the-graph means of verification—a way to prove that any piece of content, from product review to comment to news report, was indeed written by a human.

That wouldn't solve the problem of intentional disinformation; it would only solve the problem of exponentially. Limiting disinformation to that crafted by humans would leave us in the current limbo of information and disinformation doing eternal battle in the digital realms, which is likely the only acceptable outcome to begin with. We can't restrict the flow of disinformation without curating what "disinformation" consists of, and most disinformation consists in a broad gray zone of opinion, not fact—a region in which free societies must constrain themselves from meddling in.

The notion of "prove you're not a robot" would be nebulous indeed, now that we've reached the point where robots can plausibly pass for human in the narrow confines of a large language model. How do you prove you are a nonfungible human? What physical token might exist that cannot be digitized and mimicked, and how dystopian would this thing be, this "token" that proves you exist?

Again, I'm at a loss for the answers. The relevant point is not to find answers, but to observe that we're actually in a far more precarious state than we may realize. The collapse of Google, of Amazon, of Facebook, and other monopolistic giants into haphazard online messes that are increasingly hostile to their own intended purposes is not solely a problem of greed, and the battle between genuine, factual content and swarms of autogenerated versions intended to disrupt, mislead, manipulate or exploit can only end in a victory for the automated versions. No A.I. model can produce facts out of thin air; facts have costs that generative fluff does not.

And that really does seem to point to a future where information grows at a fixed or shrinking pace while automated disinformation grows at an ever-increasing one. The orbital debris problem, with large sites like Google already seeing damage that outpaces repair efforts.

A sort of Kessler Syndrome, but this one intentionally produced in order to deprive us of the easy access to knowledge that we didn't have a few decades ago but which we now take for granted. There will no doubt be efforts made to mitigate the problem—but for the life of me I can't come up with ones that are both possible and themselves nondestructive.

Provided under CC4.0 License: This essay may be republished privately or commercially in any venue so long as it is properly attributed to Hunter Lazzaro and a link to this post is included.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.