SpaceX has successfully launched its Falcon 9 rocket an amazing 454 times. Their launch cadence is such that, by the time this article goes from initial draft to publication, that number will almost certainly change. They have also successfully landed the rocket's booster stage 406 times; a feat that never stops being jaw dropping.

However, if you stop anyone in the street and ask them about SpaceX, the one thing they are likely to mention—other than CEO Elon Musk—is how their rockets keep blowing up and spraying debris across the Gulf of Mexico.

Falcon 9 is a workhorse. It enabled the Starlink internet service which now generates most of SpaceX's revenue. However, the face of the company is Starship, and that face is currently pockmarked with failures.

Not only is Starship integral to the next generation of Starlink and Musk's big Mars scheme, it's also a key component of NASA's Artemis missions to return people to the Moon. To perform any of these tasks, Starship won't just have to make a single successful flight, it will need to work over, and over, and over again with the kind of reliability that SpaceX has demonstrated with the much smaller Falcon 9.

With upgrades to ground facilities in both Texas and Florida underway to support the giant rocket, and Musk claiming that the next launch of Starship is just weeks away, it seems worth asking a simple question: Will Starship ever work, or is the whole thing a giant mistake?

A Big F**king Rocket made of carbon fiber

In 2005, Elon Musk gave his first presentation about a proposed massive rocket that would take human beings to Mars and beyond. He called it the "BFR." The letters stood for Big F**king Rocket—a joke that played off the name of a gun from the videogame Doom.

Yes. He has always been that way.

In the decade that followed, Musk regularly released teasers about the BFR, including some renders of a huge white rocket twice the height of a Saturn V and a lander with a single fin. Musk insisted that SpaceX was already at work on this beast of a machine, and each new update made space enthusiasts more ... enthusiastic.

In September 2016, Elon Musk appeared at a space conference in Mexico to introduce what was then named the "Interplanetary Transportation System" and put more details on the dream. The enormous two-stage rocket would be 17m (56') wide and stand just under 200m (650') tall. In addition to flinging a hundred colonists to Mars at a time, it would be capable of lofting an incredible 300 tons into orbit while being fully reusable.

A year later, Musk stood before another audience of space fans, interchangeably using BFR and ITS as he walked through a slide deck that contained not just technical details, but dates.

"That's not a typo," said Musk as he pointed to a slide laying out the plan to land two cargo vessels on Mars by 2022. "We've already started building the system."

A few months later, Musk showed off parts of BFR under construction, including the end domes of a massive fuel tank created from carbon-fiber composites along with some of the tooling that would allow them to construct huge cylinders of composite material.

Carbon fiber, according to Musk, was essential to the plan because it had high tensile strength and low mass. Using such lightweight materials would optimize the rocket to deliver the maximum payload to orbit and allow SpaceX to construct ships that could return to Earth over and over without requiring extensive maintenance.

But in 2019, when the first prototype conducted a hop test near Brownsville, Texas, no carbon fiber was in sight. It was all stainless steel.

Break it till you make it

By then, the massive rocket had been renamed "Starship" (confusingly, the name has been applied to the whole system as well as just the second stage, with the booster stage known as "Super Heavy"). The planned vehicle was still enormous, but it was considerably scaled back from the original 2016 edition.

Starship would be 121.3m (398') tall and 9m (30') wide. It was still bigger than a Saturn V, but compared to the original BFR design, it was much less ambitious.

There are multiple reasons why SpaceX switched from carbon fiber composites to stainless steel for Starship. Steel is much heavier, but it maintains its strength better in high-heat situations, which could help reduce the need for the kind of heat tiles that had been notoriously tricky to maintain on the Space Shuttle.

However, the simplest reason for the big change is simply cost. Building the ships out of stainless steel was almost two orders of magnitude cheaper than using carbon fiber.

That doesn't make carbon fiber an unworkable material for rockets. Competitor Rocket Labs already builds its small Electron rocket from carbon composites and will use similar materials in the much larger Neutron that it hopes to launch for the first time in 2025.

But there's a very important reason why a low-cost, easy-to-work material is vital to SpaceX. It's not what the rocket is meant to do. It's how they do their design work.

At this point, there have been eight "full stack" launches of Starship. Four of those launches have been at least partially successful. Four of them have resulted in the explosive destruction of at least one stage of the rocket.

But those launches barely scrape the surface of how SpaceX has reached this point.

The Starship that blew to glowing shreds as it neared orbit on test flight eight was actually SpaceX's 34th prototype ship. The booster that carried it was the 15th Super Heavy.

Musk's iterative development approach is spectacular to watch, but it's incredibly hardware-intensive. SpaceX built 15 prototypes of the upper stage before it got one to survive the "belly flop" maneuver that they're counting on to slow the ship during its return from space.

There's simply no way that SpaceX could have constructed 34 disposable Starships and 15 massive boosters from carbon fiber in the last six years. In addition to being technically unfeasible, using anything other than steel would have required a very different testing campaign — and it might have drained even Musk's and SpaceX's enormous resources.

This isn't how any of this works ... except at SpaceX

It's worth noting that when Blue Origin launched its first test of the New Glenn rocket earlier this year, they failed to retrieve the booster as planned. However, the upper stage reached orbit and deployed a payload, which is something Starship has not accomplished in its eight flight tests.

When Rocket Labs launches its first Neutron later this year, there's a very good chance that the upper stage of that rocket will make orbit on its first flight, even though Neutron is a complex and extremely different system than anything Rocket Labs has launched before.

However, the approach at SpaceX is, and always has been, to throw hardware at the problem until it works.

Sometimes that means everything goes right the first time (see the spectacular first launch of Falcon Heavy). Sometimes that means you spend five years crashing Falcon 9s into ships before you learn how to stick the landing.

The thing that makes this possible for SpaceX and no one else is the same thing that made stainless steel the only choice for Starship: Money. The combined wealth of Musk and SpaceX might not be bottomless, but it's pretty damn close; especially when the material cost of a steel starship (minus the engines) is likely on the order of $100,000. Musk can throw them away like tissues.

The other big requirement is compliant federal and state agencies. After a frightening failure on the first test flight, the FAA ordered SpaceX to stand down from further launches until it had conducted a full accident examination. It was six months before the ship flew again. When test flight 7 ended in a debris storm that sent planes hurrying out of the way on Jan 16, 2025, the FAA ordered another investigation. But this time Starship flew again (and blew up again) only six weeks later.

It's almost as if something happened around the end of January that made the FAA, EPA, and other federal agencies no longer an issue.

Keep that in mind if you're going to be flying near the Caribbean.

It's good to be king

Combining Musk's deep pockets with his hand over the mouth of agencies makes the situation perfect for SpaceX to continue its "hardware-rich" development program. Musk has declared that the next Starship flight will come in "about four weeks."

Compare the response of both the company and FAA to the latest flight of Blue Origin's New Glenn. That rocket's second stage performed well and placed a test system in orbit, but didn't achieve the desired recovery of the booster. The FAA opened an investigation of the Blue Origin flight on Jan. 16. That investigation was closed 77 days later on March 31.

The FAA has now given permission for Blue Origin's next test flight. The second flight of New Glenn is expected to take place around June, six months after the largely successful first flight.

SpaceX conducted its seventh test flight of Starship on Jan. 16. Despite a second-stage explosion that littered the Turks and Caicos with debris and sent aircraft scrambling, SpaceX gave permission for Starship to fly again as early as Feb. 28.

Following the explosion of the eighth test flight on March 3, SpaceX is planning another flight as early as this month (April). The FAA permit for this flight includes authorizing SpaceX to expand on previous testing by reusing a previously caught booster and/or attempting to catch a returning upper stage.

You may have heard this before but ... it's good to be king.

SpaceX has already flown Starship twice since Blue Origin launched New Glenn on Jan. 13. It's likely that Starship will fly twice more before New Glenn goes up again. So long as the FAA and other agencies are passive, and SpaceX can absorb the cost, there's absolutely no reason not to launch as many Starships as they can — because the truth is, they don't know what a Starship looks like.

Yet.

Stage 0

SpaceX isn't just tweaking the Starship from flight to flight. It's making some fairly radical revisions. The rocket that flew in Flights 7 and 8 was 3m (10') taller than the rockets in the first six text flights, and almost every internal and external component has changed. The heat shield has changed in both material and configuration. The fins the ship uses for control have been resized and moved.

SpaceX doesn't know what a functional Starship looks like. They're iterating toward something better. Hopefully. Maybe.

The thing that makes this approach feasible isn't just that Starship is made of inexpensive steel. It's that while most rockets are hand-built, artisanal items that require thousands of hours of personal attention from experienced engineers and scientists, Starship rolls off an assembly line largely manned by automated machines and former construction workers.

From the beginning, Musk and SpaceX figured that they would be making Starship in bulk – both to feed their ever-growing need for rockets to launch Starlink satellites and support Musk's ambitions of a Mars colony. In the "Star Factory" it has built in Texas, and the similar facility it's building in Florida, SpaceX has successfully moved most of the cost of its rocket to facilities that stay on the ground. The numbers may be small at the moment, but Starship is ready to be mass-produced the moment they find a workable design.

The cost of the stainless steel in a Starship upper stage is probably about the retail price of a Cybertruck — somewhere under $100,000. Internal components and electronics can be expected to run about 10 times that much. The six Raptor engines on the tail of that stage are still pricey; $1 million each, according to SpaceX.

Right now, each of those explosions over the Gulf probably means about $9 million in Starship has just gone poof. It's a lot for an average person. It's not a lot for a rocket. It's about the price of many much smaller second stages and less than the cost of the second stage that's lost on every Falcon 9 flight. It's a cost SpaceX can bear easily, even if it was happening every day.

But will it work?

Assuming nothing happens to get in the way of Musk's money pipeline, and that some schism with Trump doesn't turn the FAA into an opponent, SpaceX is going to keep launching Starships and keep changing the design in pursuit of something workable.

The task of retrieving an enormous second stage from orbit is hard. Really hard. Many times more difficult than the booster landings for either Falcon 9 or Super Heavy.

In the eight test flights, SpaceX has twice successfully brought a Starship to a relatively soft tail-down landing in the Indian Ocean. However, even if those craft had returned to Texas and been snatched out of the air, it was clear they would never fly again. Both suffered enormous and significant damage during their descent. Not even Musk would be callous enough to stick human beings into a Starship that's performed as raggedly as the ones in their first test flights. Probably.

But let's assume they fix it. Assume that, with enough money and enough flights, they can successfully launch Starship and retrieve both the booster and the orbiter at the end of a flight.

Perversely, that may be the point at which the whole scheme falls apart. Because it's not entirely clear that Starship is good for anything.

Phenomenal cosmic powers... Itty bitty payload

At one of those early presentations in 2013, SpaceX COO Gwynne Shotwell declared that Starship would be able to loft between 150 and 200 tons to low Earth orbit. SpaceX's website currently gives the capacity at 150 tons when both stages are recovered, and 250 tons when both stages were run to destruction.

But the first six starship prototypes had a theoretical capacity that maxed at 40-50 tons — less than that of Falcon Heavy. Based on information that was released when SpaceX began discussing upcoming Block 2 and Block 3 Starships, it wasn't clear the version that flew on flights 1-6 had any payload capacity at all. Yes, they had a lot of volume—a lot of empty space inside the hull—they just doesn't have the thrust and fuel necessary to carry anything substantive to orbit.

The new version, known as Block 2, reportedly has a payload capacity of 100 tons, but that's the version that has now twice blown up on its way to orbit. In the last week, Musk has insisted that the company may respond to these failures by simply moving on to an even larger Block 3 design that can theoretically loft over 200 tons.

The rocket equation is ruthless. SpaceX keeps upping the size and power of its Starship, but each time it does, most of that energy goes to simply lofting the rocket's own increased mass. The requirements of recovering the upper stage are great enough that Starship, for all its huge size, may never be capable of lofting much more than Falcon Heavy if they expect to see the upper stage come home again.

However, let's assume they do it. Let's assume that everything goes as planned and that a year from now SpaceX is able to launch and recover a Starship that can reach orbit with at least 100 tons of payload.

For many fans, this seems to be the end game. SpaceX would then have a vehicle that, assuming the cost of launch and maintenance isn't too high, would drop the price for moving a kilogram into orbit by an order of magnitude. Elon would have "won space." Mars, look out!

Except it's not that simple.

Starship, huh. Good god, y'all. What is it good for?

Following the spectacular first launch of Falcon Heavy in early 2018, it's only flown ten more times even though its little brother, Falcon 9, has made hundreds of flights.

Falcon Heavy test first flight. Note: It's always good to have friends in the film industry.

The biggest reason for Falcon Heavy's lax schedule is simple: There just are not that many things someone needs to launch into space that require a 50 ton payload capacity.

It's possible that, after watching SpaceX's giant Starship make a few successful flights, corporations will discover that they need to put something in space the size of a small building ... it's also possible that they won't. It's not clear there exists any sustained market by which SpaceX can turn a profit from Starship.

SpaceX seems to be counting on people cramming the hold of Starship with smaller satellites to spray across orbital space, and if they can offer the kind of cheap ride Musk has projected, that's likely to happen. However, there's a reason that Rocket Labs has been successful with it's small Electron rocket even though Falcon 9 has a lower cost for delivering satellites to orbit: Electron offers a custom ride to put a satellite where it's needed. A multi-satellite launch on Falcon 9 puts much higher requirements on the satellites if they need to get to a particular orbit.

That white glove service may come at the cost of a more expensive trip to space, but it can also mean that the satellites themselves are much cheaper and simpler to produce. Over 60 customers have so far made the decision to ride Electron rather than share part of a Falon 9. Other prospective launch companies, like Alpha and Firefly, have targeted smaller vehicles following this same market.

Yes, Starship is eventually intended to carry humans to infinity and beyond, but that means flying enough to get the machine safe enough to be human rated. And it means developing the orbital tanker and refueling system that Starship needs to get anywhere other than low Earth orbit.

The truth is that, for the near future at least, Starship has just one job and one customer. It will be used to deliver larger versions of Starlink to orbit. Right now, Starship isn't even designed for anything else. It has only a slot on one side that can spit out Starlink satellites fired by a giant "Pez dispenser." It has no system for releasing any other satellite, no system for refueling, and certainly nothing designed to support passengers.

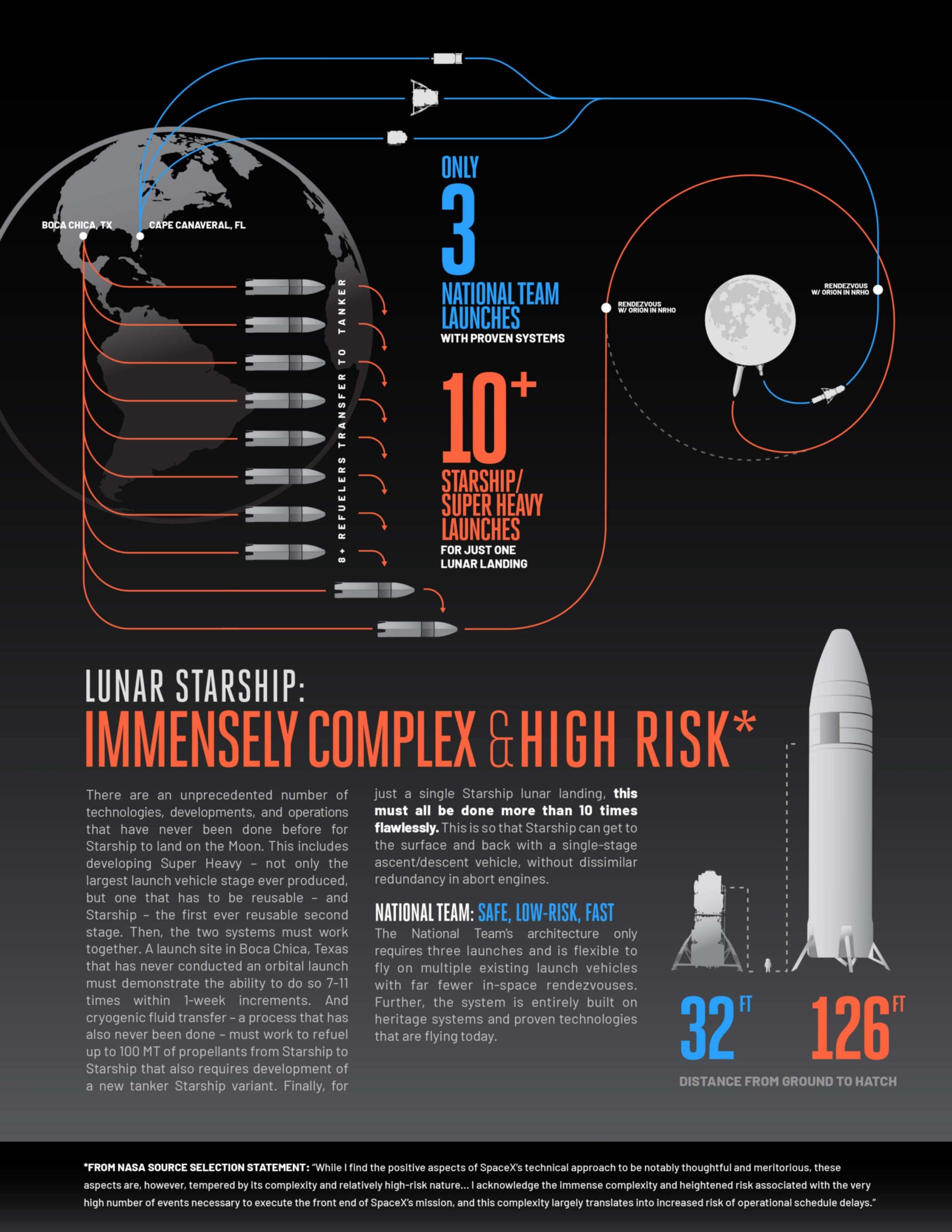

If SpaceX can solve both the reliability and the refueling problems in the next two years, Starship may be used to get the SpaceX Human Landing System (which is a highly modified version of Starship) to the Moon. But a chart that competitor Blue Origin put out in 2021 shows what a heavy lift that may be.

To complete a single lunar mission, Starship has to be reliable enough to fly at least ten times, mostly to get fuel into that (currently nonexistent) tanker. It's the rocket equation at work again. Starship is big. Steel is heavy. It takes a lot of fuel to move it around.

The difficulties in completing this task are probably a big part of why Musk is now pushing for NASA to simply skip the return to the Moon. It would take the pressure off of him to come through with the lander he took a $1.15 billion check to deliver.

If Starship can't get to orbit and back with the kind of large payloads they've been claiming, there is an alternative: They may end up making the upper stage of the rocket disposable. They can do that. It's cheap enough. But it certainly won't be as cheap, or as revolutionary, as SpaceX wanted.

These are not the answers you're looking for

In the tradition of articles whose headline ends in a question mark, the answer to whether Starship is a hoax is ... "No." Or at least, if it is, the hoax is probably being played on Musk.

Making Starship into a functional system that can operate as routinely as Falcon 9 is a much greater challenge than either Musk or his fan boys are willing to acknowledge. It may never be functional in the sense of having the reliability and capacity to complete the tasks set for it while still dropping into those big arms back at the launch pad.

In 2018, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa booked a Starship for a private flight around the Moon. In 2023, Maezawa abruptly cancelled that flight saying, "I can't plan my future in this situation."

That statement sums up just about everything involving Starship.

- SpaceX still doesn't have a final design for a ship that works as intended.

- They are conducting a rapid series of test flights in hopes that will lead them to a functional design.

- It's unclear how much payload they can actually deliver to orbit while still recovering the upper stage.

- There are many major hurdles remaining before Starship has a viable system for moving material beyond low Earth orbit.

- There are even more hurdles before that it's capable of carrying passengers.

Musk has made multiple predictions about Starship that have proved to be simply wrong. Those 2022 cargo flights to Mars didn't happen. The 2023 trip around the Moon didn't happen. He is still making predictions that seem very, very optimistic – if not actively deceptive. Like the self-driving cars that Musk promised were coming within months for over a decade, Starship's real timeline is unknown.

Starship may also not be the competition killer that many enthusiasts believe. Right now, a whole generation of new launchers, many of them years behind schedule, are finally rolling onto the stage. Vulcan and Ariane 6 have already launched and are moving toward being viable alternatives to Falcon 9. Neutron and Nova are both arguably more innovative than Starship and expected to launch some time this year.

SpaceX will likely beat the engineering problems of Starship to death through trial and error. Falcon 1 didn't get to orbit until it's fourth flight. It took 14 attempts before Falcon 9 achieved its first booster landing. The successful catches of Super Heavy show that SpaceX now has a good grasp on the problems of recovering a booster. It's just the second stage that's all new to them.

For right now, SpaceX doesn't need a customer for Starship. If it works, they can use the second stage to ferry the bigger Starlink 2 satellites into orbit for months. Even years. NASA's demands may be an issue ... but not if Musk and his new hand selected NASA administrator take those Moon flights off the board.

Musk's rocket isn't a scam. It's big, it's shiny, and eventually they'll make it work. But that doesn't mean it will dominate the industry.

And everyone who supports humanity's future in space should be happy about that.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.