Several years ago, my wife took her sixth-grade science class to Huntsville, Alabama for a week-long stay at Space Camp. Two giant bus loads of kids, five hundred miles from home, delivered the expected number of kids getting sick, girls sneaking into the boy's dorms, boys sneaking into the girl's dorms, and parents calling to complain that little Jonnie had not checked in. Plus, there was the friendship-destroying tension of finding that only some of the kids were to be trained as crew for the mission where they got to sit on the bridge of a life-size Space Shuttle and rescue a damaged satellite with the big robot arm. Others were playing much less enjoyable roles at Mission Control. A third group was stuck being, eww, scientists—an assignment that looked suspiciously like wearing a Space Camp T-shirt while doing a week of math homework.

For my perfectionist wife, this experience was very high on her Never Again list. Holding back the hair of a 12-year-old girl throwing up after a dinner of Snickers and Mtn. Dew, while fielding calls from dozens of parents who wanted to know why their precious egg wasn’t commanding the shuttle mission, was one of the middle bolgia in her personal Inferno.

For me, the week was very nearly heaven.

I got to wander most of the day through artifacts and exhibits about things that I loved. At night I would wake the boys I was supposedly chaperoning, force march them into the “rocket garden,” and treat my captive audience to lectures about the arcana of the massive vehicles around them.

Best of all, because it was late at night and there was no one around to stop me, we went everywhere. How many kids can fit inside the bell of the first-stage engine on a Saturn V? Many. Can you cross the rope, walk across the fake Moonscape (mind the craters), and climb the ladder of the LEM? You can. And it turns out to be one fairly big step for a sixth-grader.

It is debatable whether the sleepy horde I steered around the place got much from these ersatz tours. For these students, born decades after the last boot left the Moon, NASA often seemed like a boring version of Star Wars. There were no aliens, droids, or laser guns.

That's why I dragged them out there. Because it was up to me to show them this wasn't a theme park, but a museum. It was all real. From the sometimes rusting hardware around us to the stories of men and women who had Boldly Gone, these weren't props and scripts.

This was both their legacy and their future.

Part of that was explaining how everything they knew—the microprocessors that made their phones and game machines possible, the materials in their clothing and tennis shoes, even the memory foam in the mattresses they were sleeping on—was an outgrowth of the space program. Tiny motors developed for hand tools used by Apollo astronauts collecting samples on the Moon, now power drills and vacuum cleaners in almost every home. Anything with an LCD or LED screen is the result of research done for the space program. Their homes were warmer and brighter because of technology developed to support humans in space. The world they knew only existed because of what it took to build and fly those old rockets standing there in the humid Alabama darkness.

Another part of the story was explaining how many people it had taken to make this happen, and where those jobs were located. The section of the "Habitat" where we stayed was in the Thiokol wing, named for the Utah-based company that had produced both solid and liquid rocket motors for both military missiles and NASA boosters (that included the solid rocket motors used on the Challenger, and yes, we talked about that). A neighboring section of the Habitat was named for St. Louis' own McDonnell Douglas which had a big role in some of NASA's most famous craft, including the Mercury and Gemini capsules. Other areas were named for Grumman, makers of the Lunar Module; Rockwell International, the #1 contractor on both the Apollo capsule and the Space Shuttle; Lockheed, which made the SR-71 Blackbird; Martin Marietta, makers of both the Shuttle's big orange fuel tank and the Viking probes that first landed on Mars; United Technologies, which made the life support systems for the Apollo Moon suits; Boeing, which made the first spacecraft to orbit the moon and the enormous first stage of the Saturn V; and Coca-Cola, which made ... Coke.

Thiokol no longer exists. It merged with Morton (the salt guys) in the 1980s, was spun off, snapped up, and renamed multiple times over the next few decades. For a time it was part of Orbital ATK (also gone), before its last bits of intellectual property and resources were sold off ten years ago.

McDonnell Douglas no longer exists. It was bought out by Boeing in 1997 in a merger that has been infamously bad for both companies.

Rockwell International no longer exists. It was pared down, sliced up, and finally broken into parts around 2000.

Lockheed and Martin Marietta merged. The combined company sold off much of its interest in aerospace electronics, but is still solidly involved in NASA's efforts to return to the Moon.

United Technologies is gone. It merged with Raytheon in 2016, but like McDonnell's merger with Boeing, this was one of those "mergers of equals" that was really more of a buyout.

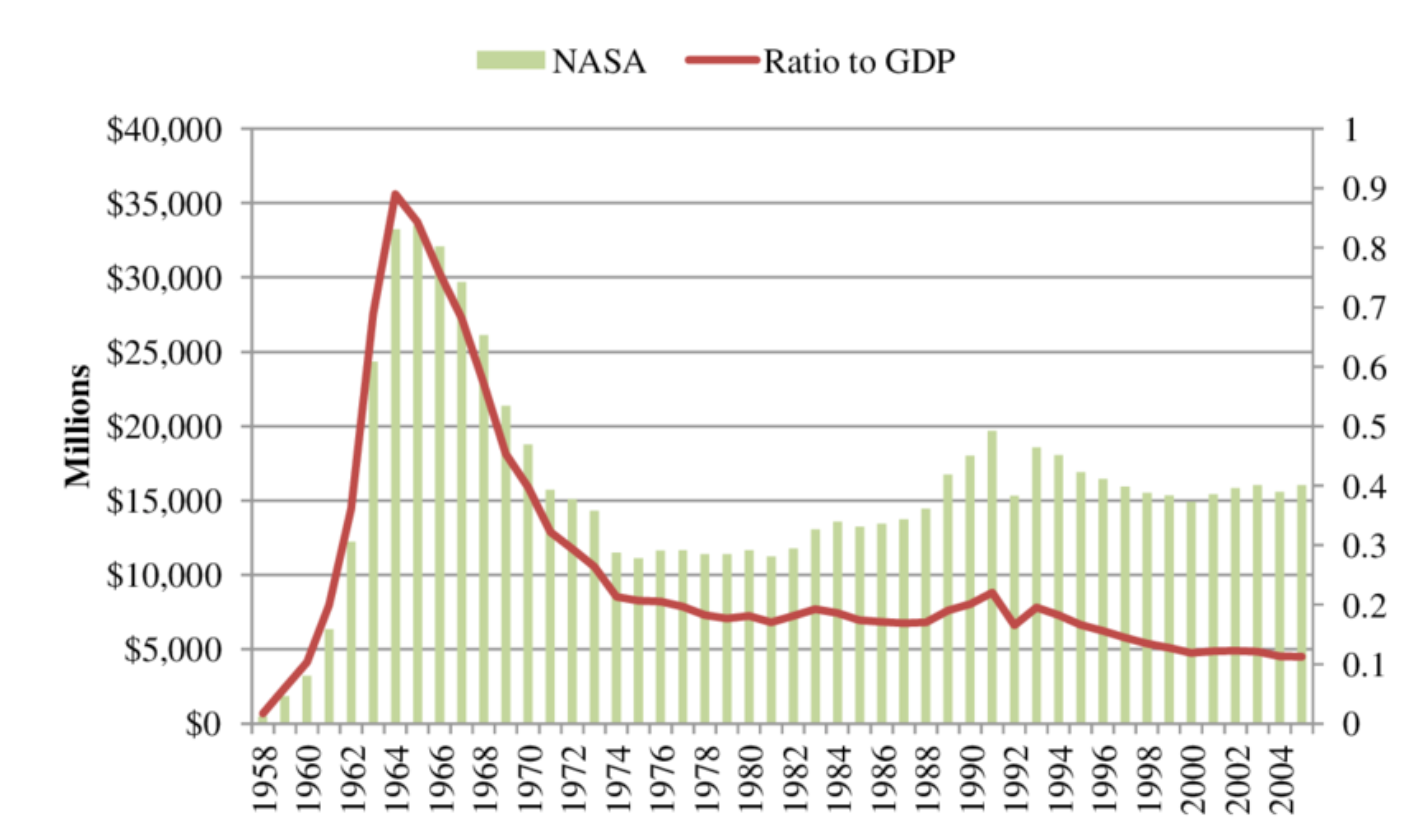

What happened to all these companies can be mostly defined by a single chart.

After the astonishing achievements of Apollo, there was never a second act. Nixon preferred to spend the money on Vietnam. Ford and Carter were left to manage massive levels of recession and inflation. Reagan's sole interest in space was in using it as a military platform. And every administration that's come after has mostly engaged in picking apart the space strategies of the one that came right before.

Through it all, Congress insisted that NASA maintain the many scattered facilities built to support that 1960s level of effort and continue to spread jobs and contracts to as many districts as possible. You can visit the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans where 3,500 people work assembling portions of the Artemis moon rocket. Or the Ames Research Center in California, where 3,200 people are engaged in aeronautical research. The Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland employs 10,000, mostly involved in the creation of satellites and deep space probes. Langley Research Center in Virginia has 3,400 NASA employees and contractors who launch smaller rockets and research the Earth's atmosphere. Stennis Space Center in Mississippi is home to 5,200 NASA workers who conduct tests on rocket engines.

These are just a few of the 10 large field centers that go from coast to coast to coast. Another 10,000 workers are found at Kennedy Space Center in Florida with 11,000 at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Overall, the agency has 18,000 direct employees, with perhaps twice that number of contractors at any given time.

NASA is often accused of being a "jobs program." If it is, it's a very good one. Many of these facilities bring well-paying, high-tech jobs into areas where comparable employment is nonexistent. Even so, it's not a patch on where NASA was during that run up to Apollo 11.

Back then, NASA had 34,000 employees and paid over 375,000 full-time contractors.

Let's sum up:

- In the 1960s space exploration was a major focus of the U.S. government.

- That focus supported hundreds of thousands of high-tech workers across the country.

- The result of that focus was a tech renaissance that created the internet, Silicon Valley, the device you're using to read this article, and incredible improvements in medical technology.

- The result of the space program wasn't just the technology that created the information age, but the wealth of engineers and scientists who went on to drive it

- When that focus was reduced, many of those jobs went away, along with the companies that government funding had helped to create.

- NASA persists as an engine of both jobs and new technology, but at a much-diminished level when compared to the past.

- NASA's ability to execute aerospace goals is limited because much of its funding goes to those many, spread-out facilities that were opened during the heyday of Apollo, and because Congress insists that projects must be spread out to create jobs in many districts.

- Congress insists that NASA be a jobs program ... and then attacks it for being a jobs program.

However, even if NASA can't fund a dozen major players and hundreds of thousands of contractors, the contracts and funds it provides are still nurturing the next wave of space exploration.

And that's exactly how we got SpaceX.

Three months after SpaceX made its first successful launch to orbit in 2008 — after three straight failed attempts — it received a NASA contract to service the International Space Station worth over $1 billion. SpaceX got that contract even though the rocket it had just launched was tiny and incapable of meeting NASA's needs. That contract was the first of many that made the Falcon 9, Dragon supply capsule, Dragon Crew Capsule, Falcon Heavy, and Starship possible.

This afternoon, SpaceX will conduct the sixth test flight of the Starship system. The fifth flight was astonishingly successful, topped off by the jaw-dropping catch of the massive "Super Heavy" booster.

Even if this sixth flight doesn't come off as planned, it's unlikely to slow SpaceX for long. The biggest reason that Musk poured millions into Trump was simply because he expects to be free of control by the FAA, EPA, and others who would interfere with his ability to conduct his business as he pleases. Under Trump, Musk expects to launch Starship hundreds of times,

The low cost to orbit Starship builds on the incredible dominance that SpaceX has already achieved in launch cadence and cost—they can do it faster, more reliably, and cheaper than anyone else. As a result, more and more government contracts, both NASA and defense, have been awarded to SpaceX.

Success for Starship opens up the Solar System for mankind. It's hard not to cheer for that. But it also places access to the system completely under the control of a single man. And that should leave everyone terrified.

It's a very easy bet that, after he gets done hopping up and down on the White House furniture, Musk will get around to informing Trump that NASA could be a lot more efficient if it closed a lot of those facilities. And canceled its second lunar lander contract with Blue Origin. And dropped launch contracts with ULA. It would all be so much more efficient if SpaceX just ran it all.

"Let SpaceX do it" is going to be an argument supported by far more people than just Musk. SpaceX has enjoyed 22 years of constantly increasing funding–including billions from NASA—and consistent goals. That’s something NASA hasn’t experienced in its best days.

The result is an operation different from anything else in the space industry. They're not building rockets like hand-crafted artisanal brioche. They're making them like Wonder Bread, turning them out in factories where they're constantly looking to cut cost and time. SpaceX is ”run like a business.”

If NASA gave every launch to SpaceX, it would be cheaper. A good case could be made that they might get back to the Moon sooner and better achieve whatever other goals are handed down from the Trump-Musk duopoly. Don't be surprised if all of that happens.

However, NASA is not a business. It was never intended to be a business. The rockets, the probes, and even the Moon landings are, at best, secondary goals.

NASA is a nursery. It's there to power America with discoveries, engineering know-how, and the technical base that keeps it competitive. NASA creates companies like SpaceX, nurtures them, and gives them the space to grow—figuratively and literally.

It's absolutely vital that NASA maintain diversity in all forms. That means diversity among its employees, dispersed facilities performing a wide array of roles, and contracts with various companies—both existing and upcoming. Even if that's not the most efficient way to get back to the Moon.

This afternoon, I'll be pulling for SpaceX as they launch Starship's sixth flight. I want to see it succeed. I want to see it move a step closer to cheap, frequent access to space.

NASA has done an excellent job in raising SpaceX. Now NASA's job should be to make sure that SpaceX is not the only fledgling to leave the nest.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.