On March 24, 2006, a small rocket launched from a U.S. military research base in the Marshall Islands. Thirty seconds later, the rocket failed, with debris raining down across the base.

That was the first launch of a startup company called Space Exploration Technologies, better known as SpaceX.

While later Elon Musk hagiographies would insist that the Falcon 1 was developed entirely using private funds, the truth is that first flight was paid for by the Defense Department. It carried a test satellite built by students at the Air Force Academy specifically designed for the Falcon 1's small capacity. That satellite crashed into the roof of a shed when the rocket met with what SpaceX likes to call "rapid unplanned disassembly."

The Defense Department also paid for the second launch of the Falcon 1. That flight lasted longer, but after five minutes, violent shaking set in and the engines shut down prematurely. It carried only a mock-up of a satellite, which was good because nothing reached orbit.

The Air Force was more confident about the next flight and loaded real satellites into the third Falcon 1. All of them were lost when the first and second stages of the rocket failed to separate about two minutes in.

That left SpaceX with just enough funding to assemble a fourth rocket made mostly from spare parts and give it one more try.

No one was confident enough to load a real satellite onto that fourth flight on September 28, 2008. Which was too bad – because that one finally worked. The Falcon 1 flew just one more time after that, on April 21, 2009, when it lofted a small Earth observation satellite for the Malaysian government. That was the only satellite that SpaceX's first rocket ever successfully deployed.

Just three months after the first flight of Falcon 1, NASA awarded SpaceX a $1.6 billion contract for 12 resupply missions to the International Space Station using the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule, neither of which existed. In 2011, Musk stated that the development cost of the Falcon 9 was around $300 million — a number easily eclipsed by the NASA funding.

In May 2012, three and a half years after making that first deal with NASA, a test Dragon capsule arrived at the ISS. SpaceX would go on to launch the Falcon 9 over 400 times. In the decade that followed, they would utterly dominate the space launch industry, easily bypassing long-standing players and revising everyone's estimates of the scale of the satellite market.

Three years after successfully delivering cargo to the ISS, a Falcon 9 booster landed on the deck of an uncrewed "drone ship." Since then, SpaceX has repeated this amazing spectacle 371 times, allowing its fleet of Falcon 9s to deliver payloads to orbit much more cheaply than anyone else. The combination of building its rockets like factory products rather than hand-crafted artisanal goods and the cost savings generated by reusing some boosters twenty times or more, has given SpaceX an edge that makes other companies seem frozen in the 1960s.

That's the SpaceX success story, and it's a good one. But it would not have happened without the DOD funding that bought those initial Falcon 1 launches and the big NASA contract that allowed SpaceX to complete development of the Falcon 9 and Dragon capsule.

Now SpaceX is an industry titan. The degree to which the company that was one launch away from disappearing now dominates the industry can be seen in the statistics from Kennedy Space Center in 2024. As of December 10, there had been 88 launches for the year — and 83 of them had been SpaceX Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy rockets.

With Musk being handed the keys by a "leader" who would rather grandstand than govern and a new NASA chief who has twice purchased flights on SpaceX rockets, there are serious concerns that the NASA's Artemis moon rocket may be at the top of the list for programs to be cut. So could the contract for Blue Origin's moon lander and launch contracts for Blue Origin, United Launch Alliance, Firefly, and Relativity Space.

In short, having gained a first-mover advantage in bringing less expensive launchers to market, Musk may now try to close the door behind him. And that would be a crime—a crime that would benefit Musk greatly but cost the nation far more.

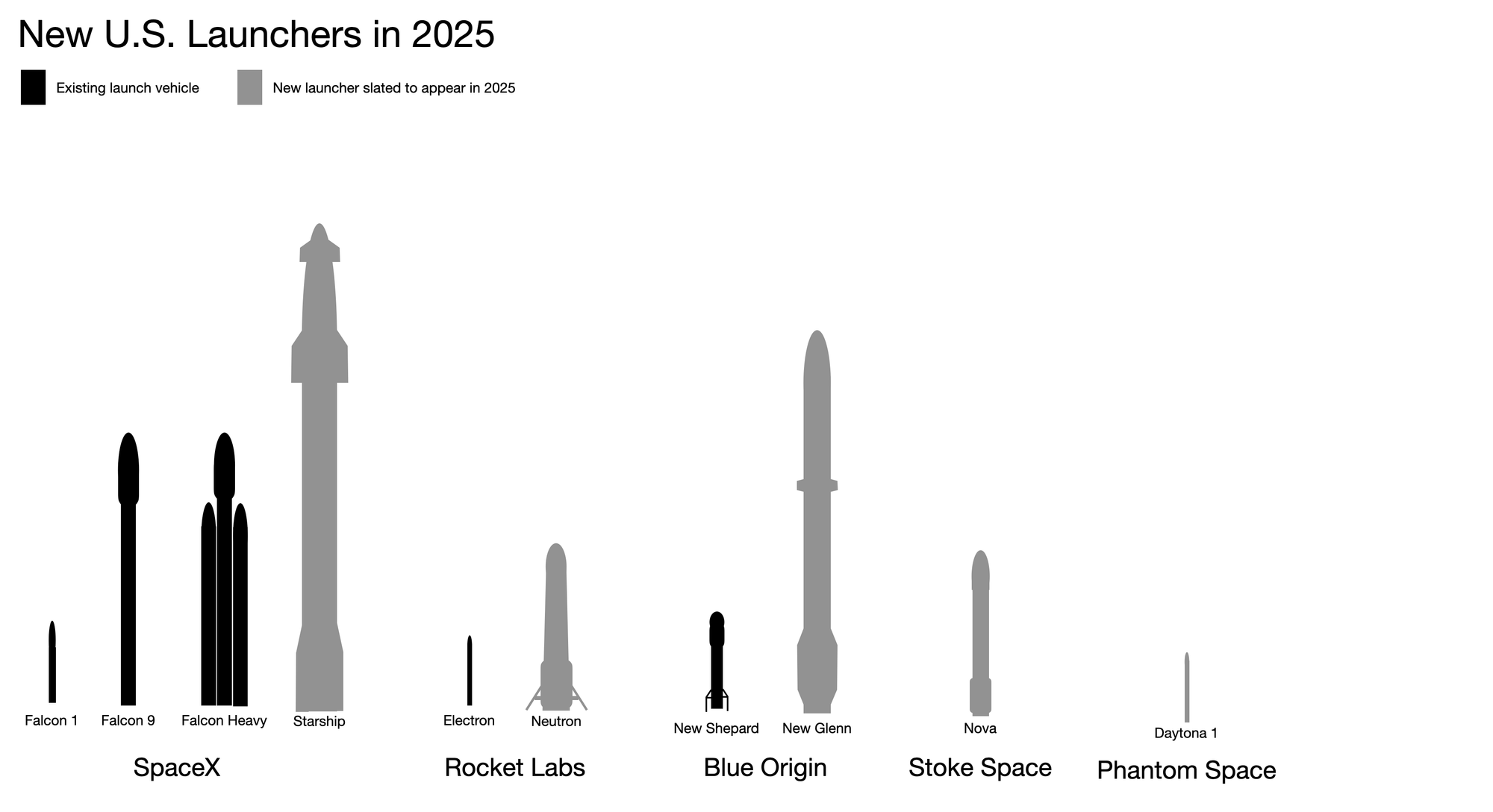

In the U.S. alone, four new launch vehicles are slated to take their first flight in 2025. Some of those rockets are set to offer the first real competition SpaceX has faced since it first landed a Falcon 9 booster in 2015. If those companies get even a fraction of the support that lifted SpaceX out of obscurity and turned it into a dominating force, access to space may not become a monopoly that hands the solar system to a single man.

Blue Origin

One of the "newcomers" is no rookie at all. Blue Origin actually got its start a year before SpaceX when Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos decided he'd like to indulge his yearning to be a space tycoon. However, where Musk and SpaceX have continually taken the "move fast and break things" approach, Bezos and Blue Origin have treated each stage of the process more like they were making Faberge eggs.

First, they developed the remarkably phallic New Shepard suborbital rocket. As an example of Blue Origin's slow approach, that rocket flew for six years before first taking people on tourist flights to the edge of space in 2021.

It has taken Blue Origin over a decade of development to get their much larger orbital rocket, New Glenn, onto the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center (which is where it is sitting at the time of this writing). If all goes according to plan, New Glenn will launch on Monday afternoon. But whether it happens Monday, within the next few days, or weeks from now (this is, after all, Blue Origin) this big rocket is worth watching.

At 98 meters tall (322'), New Glenn is roughly the same size as NASA's SLS moon rocket. Next to SpaceX's Starship, this is the biggest new rocket currently in development and it has a rated capacity of 45 tons to low Earth orbit.

What makes New Glenn particularly exciting is that, like SpaceX's Falcon 9, the booster is designed to make a powered landing for possible reuse. That potentially makes the cost-to-orbit much lower, though if Blue Origin wants to be competitive with the Falcon 9 it's going to have to step up the pace both of constructing additional New Glenns and getting them into orbit far more reguarly.

Having Bezos in space may sound no better than having Musk own the skies, but since nothing is worse than a monopoly, it's still worth crossing your fingers for New Glenn's successful launch.

On paper, Blue Origin seems set to compete with SpaceX on just about every area. They have their own satellite internet service set to be a competitor to Starlink, they have launch contracts for both civilian and military satellites, and they have that NASA contract for a lunar lander that would act as an alternative to SpaceX's Starship-based system.

Whether any of those government contracts survive Musk is an unknown.

Rocket Lab

Unlike Blue Origin, Rocket Lab actually has sent multiple rockets into orbit. Their small Electon rocket first launched in 2017 but has already made 54 successful flights carrying both civilian and government satellites to orbit.

At around $7.5 million per launch, Electron is about the cheapest route for anyone booking a custom ride to space — a Falcon 9 launch costs almost 10 times as much. However, Falcon 9 can get over 22 tonnes to orbit, while Electron can loft only about 300 kilograms. So SpaceX's cost-per-kilogram to orbit remains much lower and many small satellites go up on "ride-sharing" flights of Falcon 9 rather than get a custom boost from Electron.

Electron was not originally designed to be reusable, and while Rocket Lab has gone all out trying to recover and reuse Electron boosters, it's unlikely that the system will ever be as reliably reused as Falcon 9. That's the biggest factor that keeps Rocket Lab from further reducing their cost to orbit.

However, despite using more difficult carbon fiber for the majority of their rocket's structure, Rocket Lab has, like SpaceX, successfully created not just a launch system but a rocket factory. That experience should help them greatly as they move on to their much more capable and reusable Neutron.

In many ways, Neutron may be the most unusual launch vehicle that's set to make an appearance in 2025. Like Falcon 9 and New Glenn, only the first stage of Neutron is designed to land and launch multiple times (unlike Starship, which is ultimately designed to be fully reusable). However, the second stage of Neutron is designed to be particularly cheap and easy to build. That's because Neutron's second stage is entirely held inside the booster. The whole front end of the launcher is meant to open like an alligator's mouth, spitting out the second stage as the booster heads back for Earth.

With a target of 13 tonnes to orbit, Neutron still won't match the capacity of Falcon 9. However, Rocket Lab's bigger launcher has more than enough capacity in both size and mass to carry all but the largest satellites, and its unique design may allow it to launch for less than Falcon 9 if Rocket Lab can match its past performance in rolling out vehicles and engines.

It's easy to think of Rocket Lab as a New Zealand company. Many of their launches happen from their launch complex on the Māhia Peninsula and the company is run by enthusiastic Kiwi, Peter Beck. But the company is officially incorporated and headquartered in the U.S. — the better to garner both investments and defense contracts.

Unlike Musk and Bezos, Beck is not a tech-bro billionaire. He got his start as a tool-and-die apprentice and became a self-taught rocket engine fanatic long before starting Rocket Lab in 2006 (with the help of a New Zealand investor named Mark Rocket. Seriously). Musk may not design the rockets and engines at SpaceX, but Beck certainly has his hand in at Rocket Lab. His net worth edged $1 billion in the past year because he owns a 10% stake in Rocket Lab, but he's a rocket man who made his money being a rocket man.

Beck and his company have been reliably innovative. They've moved quickly with a lot less money than SpaceX. They may be the biggest real threat to Musk's control.

Stoke Space

Unlike Blue Origin or Rocket Lab, Stoke Space has flown exactly nothing. Well, nothing except a flight that lasted a few seconds and achieved an altitude of just a few meters.

Despite all this, Stoke Space has become a byword for excitement among space enthusiasts. They've done this with a rocket design that incorporates many of the ideas that for years (make that decades) have looked good on paper, but have proven extremely difficult in practice. And they've paired that with a low-budget, garage-built ethic that makes everyone who sees what they've accomplished feel as if maybe they could also become barnyard astronauts.

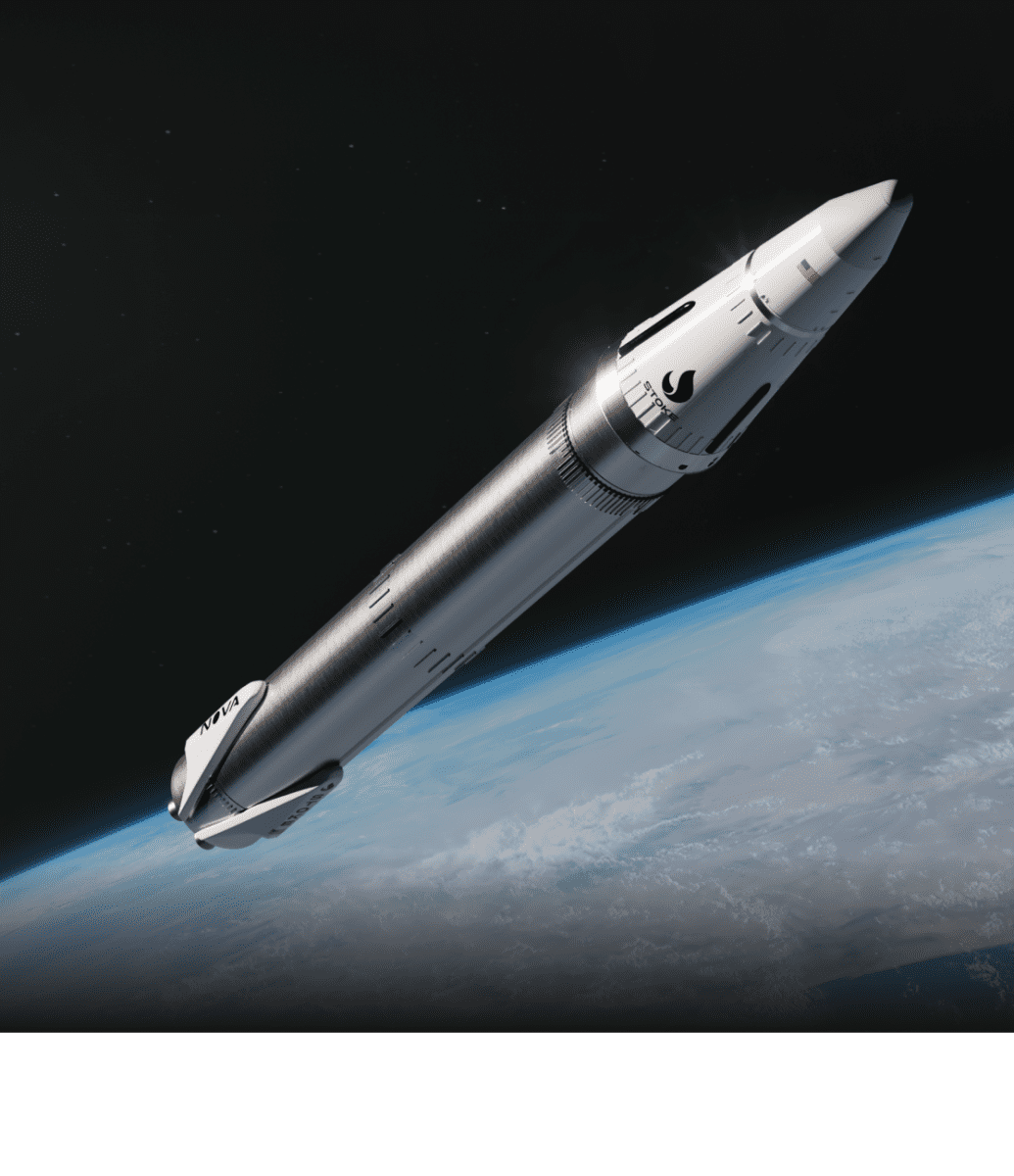

Like SpaceX's Starship, the Stoke Space Nova is designed to be fully reusable. Though its theoretical capacity is only 5 tonnes to orbit, the ability to use the entire rocket again and again could make it cheaper to fly than any other launch vehicle. And the fact that it is much smaller could make it a lot more practical than Starship for many uses.

Plus, the upper stage of Nova is designed to land under the power of 30 tiny 3D-printed boosters that form a ring around an actively cooled heat shield that altogether makes the system work like an aerospike. In terms of engineering challenges, Stoke Space hasn't quite declared "F**k it, we're just going to make a warp drive" ... but it's close.

The coolness factor of what Stoke Space is trying to do is off the charts. So is the degree of difficulty. Making this their very first launch vehicle is like trying to take on Simon Biles the first time you slipped on some leotards.

But Stoke Space was founded in 2020 by a group of former Blue Origin and SpaceX engineers who were fed up with management at their previous employers. They won a National Science Foundation grant in that first year and have been reliably hitting goals and picking up investments since. Headed by CEO Andy Lapsa, who was in charge of the development of the BE-3 and BE-4 engines at Blue Origin, the five-year-old company seems set to burst out of fanboy dream space and into actual space.

Of all the new vehicles set to appear this year, Nova is probably the least likely to stand up on a launch pad. But if it does, it may also stand the whole industry on its ear.

The other guys

These three are far from the only players in the launch industry. ULA will likely get the Vulcan flying more regularly in 2025. Phantom Space may get their small Daytona launcher into orbit. Other survivors of the "New Space" shakeout, like Firefly and Astra, are unlikely to show off anything new. None of this will do much to shake up the industry. There are also some interesting players like bluShift whose technology could make them a factor later, but are still in the early stages.

But that doesn't mean there are only three companies who are challenging Musk's right to own the Solar System. There are over 20 new launch vehicles scheduled to make their first appearance in 2025. It's just that most of them are not in the United States.

Some of these other first-timers are small, like French startup MaiaSpace and their eponymous rocket. Others, like Scotland's Skyrora, could have an impact on local markets even if they don't make a huge difference overall.

But the biggest threat to the dominance of not just Musk, but America, likely comes from China where three companies: Galactic Energy, OrienSpace, LandSpace, and CAS are all ready to follow up successful launches in 2024 with new, more powerful launchers. Of these, OrienSpace's Gravity-2 is set to deliver more mass to orbit than Falcon 9 while still bringing the booster back to the launch site for reuse. LandSpace's Zhuque-3 is set to be similar. Galactic Energy's Pallas-1 is also set to recover the booster, but it's more the size of the Electron than the Falcon 9.

Chinese rocket companies have had some spectacular failures over the past year, but they've also made amazing progress — and the Chinese government seems uninterested in slowing them down even if that means the occasional booster smashing into a neighborhood.

Those failures make good videos, but the progress of these companies is real. So is the possibility that China could quickly overtake the United States as the primary launch provider to the world.

Musk may be able to convince the government to keep Chinese cars out of the U.S. market. He won't be able to convince the world to keep Chinese rockets out of space.

How real is any of this?

Odds are that many of these rockets will not appear in 2025. Some of them will see postponements that move their first flights back a year or more. Others will never materialize at all.

First flights also have a fairly reliable track record of translating into first failures. The rocket that makes orbit the first time it hits the pad is a very rare beastie. Having a first flight that both achieves orbit and lands the booster on a barge or pad would be an incredible achievement.

Blue Origin is almost certainly going to fly the New Glenn Any Day Now. I wouldn't bet against Rocket Lab getting a Neutron into the air this year, no matter how strange it is and how many technological leaps are required — they're pretty damn good at this stuff. Everything else earns a shrug.

But the four Chinese companies discussed above are just a tiny part of an industry that's growing at an insane pace and has almost unlimited backing from the Chinese government. Don't bet against them making it work ... even if it comes with a body count.

Comments

We want Uncharted Blue to be a welcoming and progressive space.

Before commenting, make sure you've read our Community Guidelines.